Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

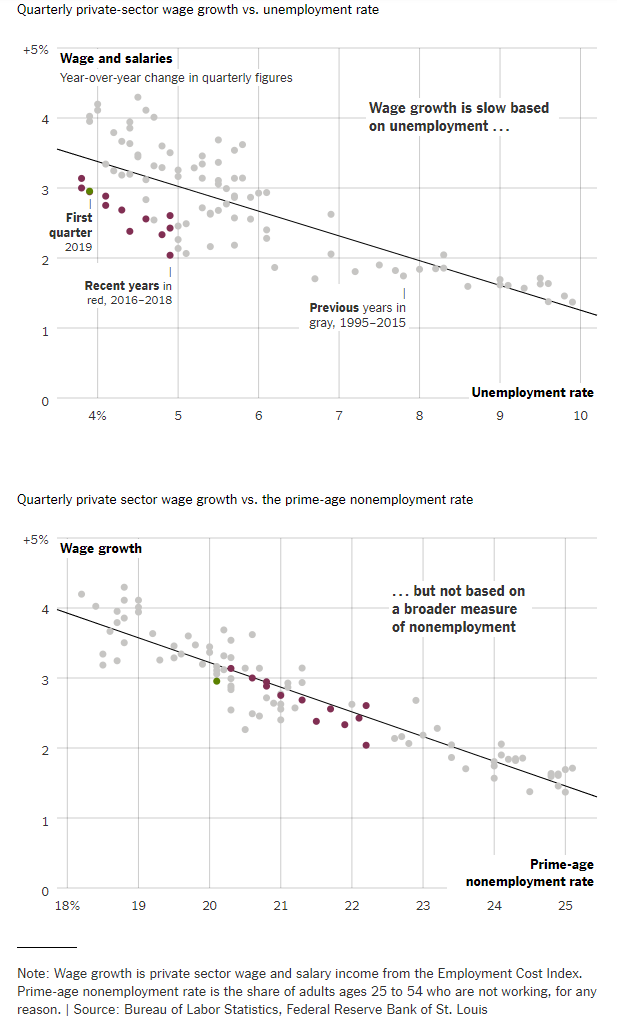

(p. B5) Many economists were puzzled by the slow pace of pay increases because it looked as if a fundamental relationship had broken down.

Decades ago, economists observed that when unemployment falls, wages tend to rise, as companies are forced to offer higher pay to attract workers. Yet even as the unemployment rate fell from 10 percent in 2009 to less than 5 percent in 2016, wages rose slowly. Even now, with the unemployment rate near multidecade lows, wages are not rising as quickly as standard models suggest they should be.

Economists proposed all sorts of theories to explain the mystery: Globalization and automation meant that Americans were competing against lower-paid workers overseas and against robots at home. The rising power of the biggest corporations, paired with falling rates of unionization, made it harder for workers to negotiate for higher pay. Sluggish productivity growth meant that companies couldn’t raise pay without eating into profits.

The recent uptick in wage growth suggests a simpler explanation: Perhaps the job market wasn’t as good as the unemployment rate made it look.

The government’s official definition of unemployment is relatively narrow. It counts only people actively looking for work, which means it leaves out many students, stay-at-home parents or others who might like jobs if they were available. If employers have been tapping into that broader pool of potential labor, it could help explain why they haven’t been forced to raise wages faster.

It appears as if that is exactly what is happening. In recent months, more than 70 percent of people getting jobs had not been counted as unemployed the previous month. That is well above historical levels, and a sign that the strong labor market is drawing people off the sidelines.

For the full story, see:

(Note: the online version of the story has the date May 2, 2019, and has the title “Why Wages Are Finally Rising, 10 Years After the Recession.”)