One of my favorite scenes in the first Harry Potter movie is when an owl tries to deliver to Harry Potter an acceptance letter to Hogwarts. Ever since Voldemort murdered Harry’s parents when he was a baby, Harry has lived under a staircase with the Dursleys (Mrs. Dursley was the sister of Harry’s mother). Mr. Dursley, and the other Dursleys too, do not like Harry, hence his living under a staircase. Mr. Dursley sees the letter to Harry, opens it, and when he realizes the contents tears it up. Then a few other copies arrive and Dursley burns them. It would appear that Harry’s hope of escape is dashed.

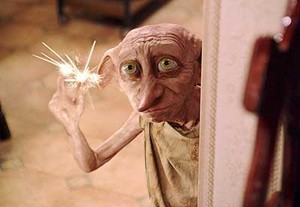

But then something wonderful. Countless owls fly toward the Dursley house, each carrying copies of the letter. Acceptance letters start pouring through the front door mail slot, down the chimney, and through every opening in the house. Soon the inside of the Dursley house is buried in acceptance letters. Dursley cannot stop Harry from knowing.

I thought of this scene when I was reading the Wikipedia entry for “Human Events.” Human Events was a smallish weekly readers-digest-type newspaper that my father subscribed to for many years (in the 1960s and 1970s?). Copies of Human Events would always be piled up next to his chair in the living room. Human Events was a contrarian publication presenting conservative/libertarian commentaries on the issues of the day.

The Wikipedia article says that starting in 1961, Ronald Reagan is an avid reader of Human Events. In the 1970s he writes articles that appear in Human Events. When he is president, Reagan’s top aides Baker, Darman, and Deaver do not like what is in Human Events, and try to keep copies of it away from him. When Reagan realizes that his aides are blocking Human Events, he “arranged for multiple copies to be sent to the White House residence every weekend” (Edwards 2011, as quoted in Wikipedia entry on “Human Events“).

Unfortunately for Reagan he does not have a flock of wise owls providing redundant information. But Reagan is his own owl.

Harry could not fire Dursley; I wonder why Reagan did not fire Baker, Darman, and Deaver?

Wikipedia gives the source of the Edwards quote as:

Edwards, Lee. “Reagan’s Newspaper.” URL: http://www.humanevents.com/article.php?id=41609