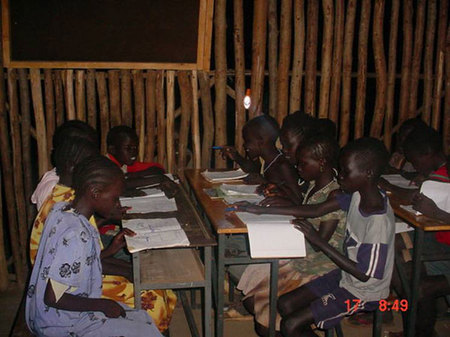

One of Mark Bent’s solar flashlights stuck in a wall to illuminate a classroom in Africa. Source of the photo: http://bogolight.com/images/success6.jpg

One of Mark Bent’s solar flashlights stuck in a wall to illuminate a classroom in Africa. Source of the photo: http://bogolight.com/images/success6.jpg

What Africa most needs, to grow and prosper, is to eject kleptocratic war-lord governments, and to embrace property rights and the free market. But in the meantime, maybe handing out some solar powered flashlights can make some modest improvements in how some people live.

The story excerpted below is an example of private, entrepreneur-donor-involved, give-while-you-live philanthropy that holds a greater promise of actually doing some good in the world, than other sorts of philanthropy, or than government foreign aid.

FUGNIDO, Ethiopia — At 10 p.m. in a sweltering refugee camp here in western Ethiopia, a group of foreigners was making its way past thatch-roofed huts when a tall, rail-thin man approached a silver-haired American and took hold of his hands.

The man, a Sudanese refugee, announced that his wife had just given birth, and the boy would be honored with the visitor’s name. After several awkward translation attempts of “Mark Bent,” it was settled. “Mar,” he said, will grow up hearing stories of his namesake, the man who handed out flashlights powered by the sun.

Since August 2005, when visits to an Eritrean village prompted him to research global access to artificial light, Mr. Bent, 49, a former foreign service officer and Houston oilman, has spent $250,000 to develop and manufacture a solar-powered flashlight.

His invention gives up to seven hours of light on a daily solar recharge and can last nearly three years between replacements of three AA batteries costing 80 cents.

Over the last year, he said, he and corporate benefactors like Exxon Mobil have donated 10,500 flashlights to United Nations refugee camps and African aid charities.

Another 10,000 have been provided through a sales program, and 10,000 more have just arrived in Houston awaiting distribution by his company, SunNight Solar.

“I find it hard sometimes to explain the scope of the problems in these camps with no light,” Mr. Bent said. “If you’re an environmentalist you think about it in terms of discarded batteries and coal and wood burning and kerosene smoke; if you’re a feminist you think of it in terms of security for women and preventing sexual abuse and violence; if you’re an educator you think about it in terms of helping children and adults study at night.”

Here at Fugnido, at one of six camps housing more than 21,000 refugees 550 miles west of Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, Peter Gatkuoth, a Sudanese refugee, wrote on “the importance of Solor.”

“In case of thief, we open our solor and the thief ran away,” he wrote. “If there is a sick person at night we will took him with the solor to health center.”

A shurta, or guard, who called himself just John, said, “I used the light to scare away wild animals.” Others said lights were hung above school desks for children and adults to study after the day’s work.

For the full story, see:

(Note: the title of the article on line was: "Solar Flashlight Lets Africa’s Sun Deliver the Luxury of Light to the Poorest Villages.")

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

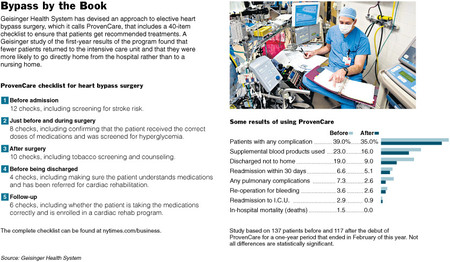

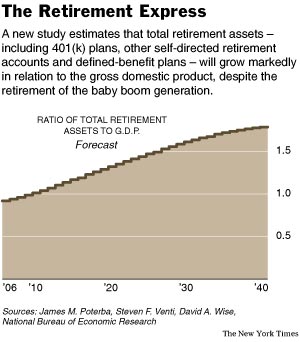

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.