(p. B16) James F. Holland, a founding father of chemotherapy who helped pioneer a lifesaving drug treatment for pediatric leukemia patients, died on Thursday [March 22, 2018] at his home in Scarsdale, N.Y.

. . .

“Patients have to be subsidiaries of the trial,” he told The New York Times in 1986. “I’m not interested in holding patients’ hands. I’m interested in curing cancer.”

He acknowledged that some patients become guinea pigs, and that they sometimes suffer discomfort in the effort to eradicate tumors, but he said that even those who die provide lessons for others who will survive.

“If you do no harm,” Dr. Holland said, “then you do no harm to the cancer, either.”

. . .

Dr. Holland acknowledged that while experimenting with drug treatment sometimes amounts to trial and error, the primary killer is typically the disease itself.

“The thing to remember,” he said, “is that the deadliest thing about cancer chemotherapy is not the chemotherapy.” Continue reading ““If You Do No Harm, Then You Do No Harm to the Cancer, Either””

Category: Books

Big, Frequent Meetings Are Unproductive and Crowd Out Deep Thought

(p. 7) To figure out why the workers in Microsoft’s device unit were so dissatisfied with their work-life balance, the organizational analytics team examined the metadata from their emails and calendar appointments. The team divided the business unit into smaller groups and looked for differences in the patterns between those where people were satisfied and those where they were unhappy.

It seemed as if the problem would involve something about after-hours work. But no matter how Ms. Klinghoffer and Mr. Fuller crunched the data, there weren’t any meaningful correlations to be found between groups that had a lot of tasks to do at odd times and those that were unhappy. Gut instincts about overwork just weren’t supported by the numbers.

The two kept iterating until something emerged in the data. People in Mr. Ostrum’s division were spending an awful lot of time in meetings: an average of 27 hours a week. That wasn’t so much more than the typical team at Microsoft. But what really distinguished those teams with low satisfaction scores from the rest was that their meetings tended to include a lot of people — 10 or 20 bodies arrayed around a conference table coordinating plans, as opposed to two or three people brainstorming ideas.

The issue wasn’t that people had to fly to China or make late-night calls. People who had taken jobs requiring that sort of commitment seemed to accept these things as part of the deal. The issue was that their managers were clogging their schedules with overcrowded meetings, reducing available hours for tasks that rewarded more focused concentration — thinking deeply about trying to solve a problem.

Data alone isn’t insight. But once the Microsoft executives had shaped the data into a form they could understand, they could better question employees about the source of their frustrations. Staffers’ complaints about spending evenings and weekends catching up with more solitary forms of work started to make more sense. Now it was clearer why the first cuts of the data didn’t reveal the problem. An engineer sitting down to do individual work for several hours on a Saturday afternoon probably wouldn’t bother putting it on her calendar, or create digital exhaust in the form of trading emails with colleagues during that time.

Anyone familiar with the office-drone lifestyle might scoff at what it took Microsoft to get here. Does it really take that much analytical firepower, and the acquisition of an entire start-up, to figure out that big meetings make people sad?

For the full story, see:

(Note: the online version of the story has the date June 15, 2019, and has the title “The Mystery of the Miserable Employees: How to Win in the Winner-Take-All Economy.”)

The article quoted above, is adapted from:

Irwin, Neil. How to Win in a Winner-Take-All World: The Definitive Guide to Adapting and Succeeding in High-Performance Careers. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2019.

To Be Dangerous with Crispr Takes a Lot of Genetics Knowledge

(p. A11) “I frankly have been flabbergasted at the pace of the field,” says Jennifer Doudna, a Crispr pioneer who runs a lab at the University of California, Berkeley. “We’re barely five years out, and it’s already in early clinical trials for cancer. It’s unbelievable.”

. . .

Scientists have fiddled with genes for decades, but in clumsy ways.

. . .

Crispr is much more precise, as Ms. Doudna explains in her new book, “A Crack in Creation.” It works like this: An enzyme called Cas9 can be programmed to latch onto any 20-letter sequence of DNA. Once there, the enzyme cuts the double helix, splitting the DNA strand in two. Scientists supply a snippet of genetic material they want to insert, making sure its ends match up with the cut strands. When the cell’s repair mechanism kicks in to fix the cut, it pastes in the new DNA.

. . .

A . . . Crispr worry is that it makes DNA editing so easy anybody can do it. Simple hobby kits sell online for $150, and a community biotech lab in Brooklyn offers a class for $400. Jennifer Lopez is reportedly working on a TV drama called “C.R.I.S.P.R.” that, according to the Hollywood Reporter, “explores the next generation of terror: DNA hacking.”

Ms. Doudna provides a bit of assurance. “Genetics is complicated. You have to have quite a bit of knowledge, I think, to be able to do anything that’s truly dangerous,” she says. “There’s been a little bit of hype, in my opinion, about DIY kits and are we going to have rogue scientists—or even nonscientists—randomly doing crazy stuff. I think that’s not too likely.”

For the full interview, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the interview has the date July 7, 2017, and the same title as the print versio.)

Doudna’s book, mentioned above, is:

Doudna, Jennifer A., and Samuel H. Sternberg. A Crack in Creation: Gene Editing and the Unthinkable Power to Control Evolution. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017.

Clayton Christensen Wrongly Predicted Bombardier Would Disrupt Boeing

Clayton Christensen and co-authors predicted in Seeing What’s Next that Bombardier was well-positioned to use disruptive innovation to leapfrog Boeing and Airbus.

(p. B8) Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. said it would acquire Bombardier Inc.’s regional-jet business for $550 million in a transaction that puts the companies on different paths in the aviation sector.

The deal unveiled Tuesday [June 25, 2019] marks the Canadian company’s exit from the commercial passenger-aircraft business following failed bets that it could compete with Airbus SE and Boeing Co. in the 100-seat single-aisle plane category.

Bombardier has restructured its aviation division over the past two years, highlighted by its joint venture with Airbus that put the European plane maker in charge of the production and sales of the 110- to 130-seat planes that the Montreal company had originally conceived as the CSeries. Those jets are now rebranded as the Airbus A220.

For the full story, see:

Vieira, Paul. “Bombardier to Sell Jet Unit.” The Wall Street Journal (Wednesday, June 26, 2019): B8.

(Note: bracketed date added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the same date June 25, 2019, and has the title “Mitsubishi to Acquire Bombardier’s Regional Jet Unit for $550 Million.”)

The Christensen book mentioned above, is:

Christensen, Clayton M., Scott D. Anthony, and Erik A. Roth. Seeing What’s Next: Using Theories of Innovation to Predict Industry Change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2004.

iPhone Made Internet “Almost Ubiquitous”

(p. B3) By essentially compressing a powerful, networked computer into a pocket-size device and making it easy to use, Steve Jobs made the internet almost ubiquitous and fundamentally altered decades-old consumer habits in areas like music and books. What’s more, the functionality packed into the iPhone made it a digital Swiss Army knife, supplanting existing tools from email to calendar to maps to calculators.

. . .

Along the way, smartphones disrupted communication. By offering faster, easier ways to communicate—text, photo, video and social networks—“the iPhone destroyed the phone call,” says Joshua Gans, professor at the University of Toronto and author of the book, “The Disruption Dilemma.” “It’s funny we even call it a phone.”

For the full story, see:

Betsy Morris. “What the iPhone Wrought.” The Wall Street Journal (Saturday, June 24, 2017): B3.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date June 23, 2017, and the title “From Music to Maps, How Apple’s iPhone Changed Business.”)

The Gans book mentioned above, is:

Gans, Joshua. The Disruption Dilemma. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2016.

“Only 5% to 10% of Jobs Can Have the Human Element Removed Entirely”

(p. A15) Careful studies using a task-based view of this sort find that, although substantial parts of many jobs can be automated—that is, technology can help still-needed workers become more productive—only 5% to 10% of jobs can have the human element removed entirely. The rate of productivity growth implied by the coming wave of automation would thus look similar to historical rates.

. . .

. . . the best insights into the future of work may be found in the trenches of everyday management. Take “Human + Machine,” by Accenture leaders Paul Daugherty and Jim Wilson, which opens in a BMW assembly plant where “a worker and robot are collaborating.” In their view, “machines are not taking over the world, nor are they obviating the need for humans in the workplace.”

The authors explain, for instance, why making robots operate more safely alongside humans has been critical to factory deployment—the very breakthrough emphasized by Dynamic’s CEO, but ignored by Mr. West. They describe AI’s role alongside existing workers in decidedly unsexy fields like equipment maintenance, bank-fraud detection and customer complaint management. And they illuminate the promise and pitfalls of implementing new processes that allocate some tasks to machines, requiring new forms of oversight and coordination.

Even in their overuse of acronyms and the word “reimagine,” the authors bring to life the realities of modern management. Readers gain a tactile sense of how technology changes business over time and why “the robots are coming” is no scarier an observation than ever before.

For the full review, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date June 24, 2018, and has the title “BOOKSHELF; ‘The Future of Work’ and ‘Human + Machine’ Review: Reckoning With the Robots; Automation rarely outright destroys jobs. It instead augments—taking over routine tasks while humans handle more complex ones.”)

The book under review, in the passages above, is:

Daugherty, Paul R., and H. James Wilson. Human + Machine: Reimagining Work in the Age of AI. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2018.

New Opiod Regulations Make Life Harder for Those in Severe Pain

(p. C4) There’s a great deal in “Dopesick” that’s incredibly bleak, but the most chilling moment for me was a quote from one of Macy’s journalist friends. Synthetic opioids had allowed this woman, despite a severe curvature of her spine, to lead an active life without risky surgery. She resented new rules that made it more onerous for her to get the pills. “My life,” she told Macy, “is not less important than that of an addict.”

For the full review, see:

Jennifer Szalai. “BOOKS OF THE TIMES; A Ground-Level Look At the Opioid Epidemic.” The New York Times (Thursday, July 26, 2018): C1 & C4.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date July 25, 2018, and has the title “BOOKS OF THE TIMES; ‘Dopesick’ Traces the Opioid Crisis, From Beginning to Blow Up.”)

The book under review, is:

Macy, Beth. Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company That Addicted America. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2018.

Lacking Absolute Certainty, Evidence Can Get Us to “True Enough”

(p. A17) As in his earlier books, Mr. Blackburn displays a rare combination of erudite precision and an ability to make complex ideas clear in unfussy prose.

If truth has seemed unattainable, he argues, it is because in the hands of philosophers such as Plato and Descartes it became so purified, rarefied and abstract that it eluded human comprehension. Mr. Blackburn colorfully describes their presentation of truth as a “picture of an entirely self-enclosed world of thought, spinning frictionless in the void.”

The alternative is inspired by more grounded philosophers, like David Hume and especially the American pragmatists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries: Charles Sanders Peirce, William James and John Dewey. Mr. Blackburn repeatedly returns to a quote from Peirce that serves as one of the book’s epigraphs: “We must not begin by talking of pure ideas—vagabond thoughts that tramp the public highways without any human habitation—but must begin with men and their conversation.” The best way to think about truth is not in the abstract but in media res, as it is found in the warp and weft of human life.

Put crudely, for the pragmatists “the proof of the pudding is in the eating.” We take to be true what works. Newton’s laws got us to the moon, so it would be perverse to deny that they are true. It doesn’t matter if they are not the final laws of physics; they are true enough. “We must remember that a tentative judgment of truth is not the same as a dogmatic assertion of certainty,” says Mr. Blackburn, a sentence that glib deniers of the possibility of truth should be made to copy out a hundred times. Skepticism about truth only gets off the ground if we demand that true enough is not good enough—that truth be beyond all possible doubt and not just the reasonable kind.

For the full review, see:

(Note: the online version of the review has the date July 24, 2018, and has the title “BOOKSHELF; ‘On Truth’ Review: Beyond a Reasonable Doubt; A philosopher argues that truth is humble, not absolute: “A tentative judgment . . . is not the same as a dogmatic assertion of certainty”.”)

The book under review is:

Blackburn, Simon. On Truth. Reprint ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Astros Got Scouting and Analytics to Work Together

(p. A15) Mr. Reiter . . . has written a full account of the remarkable story of how one of the greatest turnarounds in modern baseball history was engineered. As he tells us in “Astroball: The New Way to Win It All,” Houston had looked at the processes that Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane had used early in the 21st century. That team’s methods—sophisticated statistical analyses and attention to “undervalued” measuring sticks (like on-base percentage)—were detailed in Michael Lewis’s “Moneyball” (2003), and they changed the way baseball front offices operated. But Mr. Lewis’s book also portrayed a somewhat fraught internal organization, with old-fashioned scouts in one corner and the analytic nerds in the other, often disagreeing about players and prospects and resenting one another as well.

Astros general manager Jeff Luhnow wanted to figure out how to get scouting and analytics to work together and eventually produce an internal metric that would render a decision on a player as simple as the one in blackjack: hit or stay, keep or trade, play or bench.

. . .

Under Mr. Luhnow, scouts not only made subjective judgments about a prospect’s talent but also collected unique data that they fed to the folks in the Nerd Cave. And the nerds began listening to the scouts. All of this was easier said than done, but it was done, and the team made a series of sound, even brilliant, choices as it drafted, traded and signed players.

For the full review, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date July 16, 2018, and has the title “BOOKSHELF; ‘Astroball’ Review: Lone Star Turnaround

How the Houston Astros used a combination of data-driven analytics and team-building to go from last place to World Series champions.”)

The book under review is:

Reiter, Ben. Astroball: The New Way to Win It All. New York: Crown Archetype, 2018.

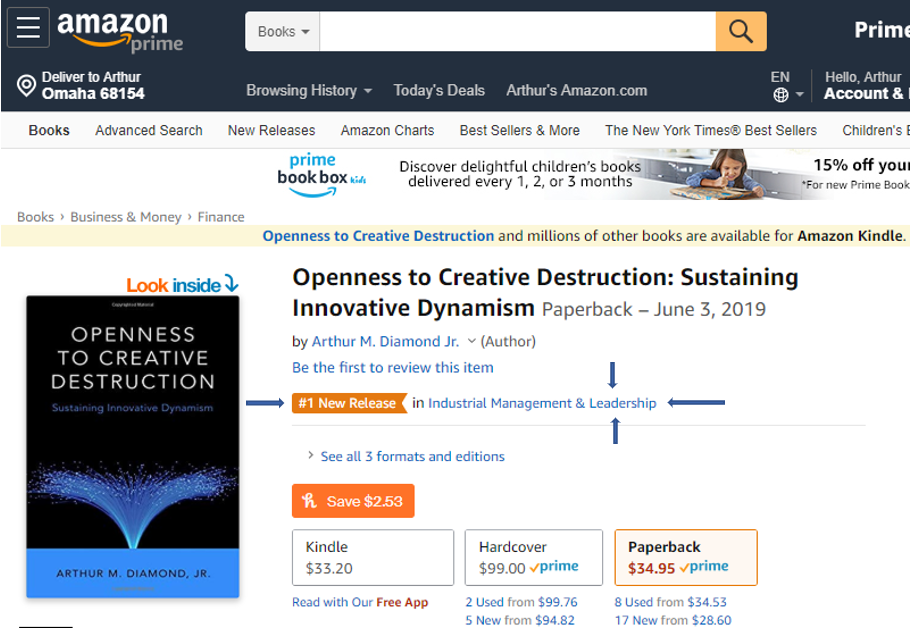

Reason Magazine Runs Excerpt from “Openness to Creative Destruction”

Innovative dynamism creates more jobs than it destroys and the new jobs created are usually better jobs than the old jobs destroyed. The Aug./Sept. issue of Reason includes an edited excerpt of this positive account of the labor market from Openness to Creative Destruction. The online version of the article is available now. The print version of the article either is on newsstands now, or will be soon. The citation for the article is:

Diamond, Arthur M., Jr. “How Work Got Good.” Reason (Aug./Sept. 2019): 22-24.