Source of book image: online version of the WSJ review quoted and cited below.

Spencer was sometimes a much better philosopher than the modern caricature portrays, a caricature exemplified by the review quoted below and, perhaps, by the book reviewed. I would like to look at this book sometime, because there may be some interesting history in it—though I am not optimistic about the book’s economic assumptions, or its account of Spencer’s philosophy.

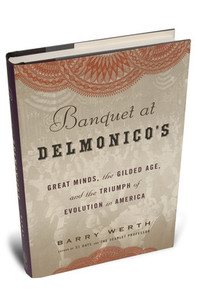

(p. A11) Herbert Spencer, the 19th-century British philosopher, is remembered today as the forbidding — almost forbidden — father of “Social Darwinism,” a school of thought declaring that the fittest prosper in a free marketplace and the human race is gradually improved because only the strong survive. In Barry Werth’s satisfying “Banquet at Delmonico’s,” Spencer is also a querulous 62-year-old celibate whose 1882 American tour culminates in a feast to which are invited the “mostly Republican men of science, religion, business, and government” who shared and spread the Spencerian creed.

Applying Darwinian insights about evolution to political, economic and social life — though he did not himself use the term “Social Darwinism” — Spencer concluded that vigorous competition and unfettered capitalism conduced to the betterment of society. He predicted that the American, raised in liberty, would evolve into “a finer type of man than has hitherto existed,” dazzling the world with “the highest form of government” and “a civilization grander than any the world has known.”

. . .

The public clamor over the visit of a dyspeptic foreign philosopher to these shores was partly due to the indefatigable promotion of Edward Livingston Youmans, Spencer’s chief American proselytizer, who called his beau ideal the most original thinker in the history of mankind. Youmans is among the several critics and apostles of Spencer and Darwin whose profiles Mr. Werth skillfully interweaves in this Gilded Age tapestry.

For the full review, see:

BILL KAUFFMAN. “BOOKSHELF; Darwin in the New World; When the father of Social Darwinism came to America, the place where the fittest were supposed to thrive.” The Wall Street Journal (Fri., January 9, 2009): A11.

(Note: ellipsis added; italics in original.)

The book under review is:

Werth, Barry. Banquet at Delmonico’s: Great Minds, the Gilded Age, and the Triumph of Evolution in America. New York: Random House, 2009.

For a more balanced account of Spencer, see the first review below for the mostly good in Spencer, and the second review below for the mostly bad in Spencer:

Diamond, Arthur M., Jr. “Spencer’s Tragedy: Review of Herbert Spencer’s The Principles of Ethics.” Modern Age 24, no. 4 (Fall 1980): 419-421.

Diamond, Arthur M., Jr. “The State of Spencer: Review of Herbert Spencer’s The Man Versus the State.” Modern Age 28, nos. 2-3 (Spring/Summer 1984): 286-288.