Engineer Benedikt Thoma is moving his family to Canada from Germany for a brighter future. Source of photo: online verion of the NYT article cited below.

Engineer Benedikt Thoma is moving his family to Canada from Germany for a brighter future. Source of photo: online verion of the NYT article cited below.

ESCHBORN, Germany, Feb. 3 — Benedikt Thoma recalls the moment he began to think seriously about leaving Germany. It was in 2004, at a New Year’s Day reception in nearby Frankfurt, and the guest speaker, a prominent politician, was lamenting the fact that every year thousands of educated Germans turn their backs on their homeland.

“That struck me like a bolt of lightning,” said Mr. Thoma, 44, an engineer then running his family’s elevator company. “I asked myself, ‘Why should I stay here when the future is brighter someplace else?’ ”

In December, as his work with the company became an intolerable grind because of labor disputes, Mr. Thoma quit and made plans to move to Canada. In its wide-open spaces he hopes to find the future that he says is dwindling at home. As soon as he lands a job, Mr. Thoma, his wife, Petra, and their two teenage sons will join the ranks of Germany’s emigrants.

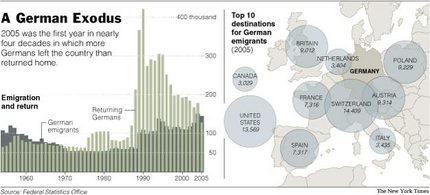

There has been a steady exodus over the years, but it has recently become Topic A in a land already saddled with one of the most rapidly aging and shrinking populations of any Western nation. With evidence that more professionals are leaving now than in past years, politicians and business executives warn about the loss of their country’s best and brightest.

. . .

. . . , there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that Germany has become less attractive for people in fields like medicine, academic research and engineering. Those who leave cite chronic unemployment, a rigid labor market, stifling bureaucracy, high taxes and the plodding economy — which, though better recently, still lags behind that of the United States.

. . .

In Mr. Thoma’s view, the root of the problem is [that] . . . Germany, . . . , has a “blockage” in its society.

“Germans are so complacent,” he said, sitting at the dining table in his neat-as-a-pin home here. “They don’t want to change anything. Everything is discussed endlessly without ever reaching a solution.”

As an example he cites the stalemate between his family’s firm and its 89 employees. After the firm became unionized, he said, the two sides began bickering over wages and working conditions.

With much of his 80-hour workweeks eaten up by those disputes, Mr. Thoma said he had developed high blood pressure and other ailments. He told his brothers he was burned out and ready to leave.

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

Source of graphic: online verion of the NYT article cited above.

Source of graphic: online verion of the NYT article cited above.