Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

(p. 1) TALK to Kenneth Doolittle about General Motors, where he once supervised a team of assembly line workers, and he readily speaks with pride about his job and the self-esteem it provided. “I loved all of it — the people, the work,” he says. “I was in a position finally where people listened to me when I spoke. I wasn’t just a Joe-Nobody. I contributed.”

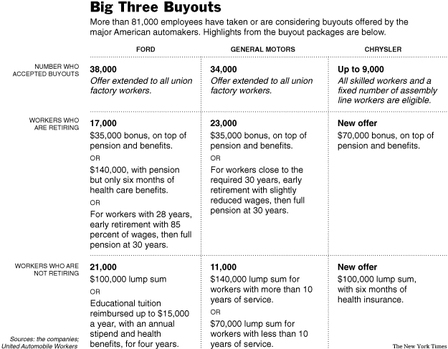

Talk to Mr. Doolittle a little longer and he gradually describes why he decided to take a buyout from G.M. — joining more than 80,000 Big Three employees in the largest exodus of workers from a single American industry in decades.

. . .

The exodus that Mr. Doolittle is joining is voluntary. Some have changed their minds. More than 3,000 workers who signed up over the last year to leave Ford and G.M. subsequently decided to stay. These are, after all, the highest-paying blue-collar jobs left in America. Even so, workers are departing from the auto industry en masse, escaping — as they put it in interviews — increasingly difficult working conditions at companies they fear will desert them.

. . .

(p. 9) When G.M. decided to close his plant in 2005, Mr. Doolittle’s seniority gave him every right to transfer to a much newer factory right next door, where G.M. is building a popular Cadillac sedan and is likely to do so for as long as Mr. Doolittle might have wanted a job. But he balked because of the change in stature that would accompany the switch.

Since his departure last year, he has struggled to occupy his time. Divorced, with four grown children, he divides his days between an apartment in Lansing and a trailer parked on a small lakefront plot that he owns north of the city. He has typed out on a laptop three novels “about my life experience.” And to make up some of his lost income — his $36,000 pension is 60 percent of his old pay — he works 20 hours a week, at $10 an hour, doing maintenance at Sears stores.

“That is just enough to keep me from watching Jerry Springer every day,” he said. “I don’t want to sit in front of a TV; I’m too young for that.”

. . .

Across America, more than 30 million people have been forced out of jobs since the early 1980s, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports, and regaining lost incomes has not been easy. Nearly 50 million new jobs have been created over that same period, according to the bureau, so there are always new opportunities but more often than not at lower pay. Among those who have lost work, only a third held new jobs two years later that paid as well as those that were lost, according to the bureau’s surveys of displaced workers. Another third of those displaced were in jobs that paid, on average, 15 to 20 percent less than their previous employment — while the final third had dropped out of the labor force entirely.

The Census Bureau reported a jump in net migration out of Michigan last year: some 42,300 people left, up from 29,700 in 2005. That was far and away the largest outflow from the state since 1984, during the Rust Belt crisis, census data show. . . .

. . .

The exodus is reminiscent of the Dust Bowl migration from the prairie states in the 1930s, when unemployed farmers gave up and trekked west to California. The Dust Bowl migration, on its face, was much more brutal — the number of displaced Okies, as they were called, was far greater than the current number of departing auto workers, and there were not corporate and public subsidies at the time to soften the hardship.

“The Okies did not know whether they would get to their destination before they starved to death,” said Daniel Luria, an economist at the Michigan Manufacturing Technology Center. “The labor market prospects for the auto workers are not good, but they have assets. They are not in danger of immediately falling into poverty.”

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

Novelist Kenneth Doolittle. Source of photo: screen capture from online version of the NYT article cited above.

Novelist Kenneth Doolittle. Source of photo: screen capture from online version of the NYT article cited above.