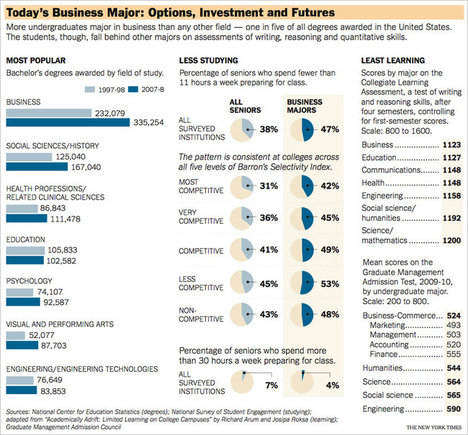

The above table shows that business is a popular major, but that students who major in business tend to spend less time studying than other majors, and also tend to learn less than other majors.

The above table shows that business is a popular major, but that students who major in business tend to spend less time studying than other majors, and also tend to learn less than other majors.

(p. 16) PAUL M. MASON does not give his business students the same exams he gave 10 or 15 years ago. “Not many of them would pass,” he says.

Dr. Mason, who teaches economics at the University of North Florida, believes his students are just as intelligent as they’ve always been. But many of them don’t read their textbooks, or do much of anything else that their parents would have called studying. “We used to complain that K-12 schools didn’t hold students to high standards,” he says with a sigh. “And here we are doing the same thing ourselves.”

That might sound like a kids-these-days lament, but all evidence suggests that student disengagement is at its worst in Dr. Mason’s domain: undergraduate business education.

Business majors spend less time preparing for class than do students in any other broad field, according to the most recent National Survey of Student Engagement: nearly half of seniors majoring in business say they spend fewer than 11 hours a week studying outside class. In their new book “Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses,” the sociologists Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa report that business majors had the weakest gains during the first two years of college on a national test of writing and reasoning skills. And when business students take the GMAT, the entry examination for M.B.A. programs, they score lower than students in every other major.

. . .

(p. 17) IN “Academically Adrift,” Dr. Arum and Dr. Roksa looked at the performance of students at 24 colleges and universities. At the beginning of freshman year and end of sophomore year, students in the study took the Collegiate Learning Assessment, a national essay test that assesses students’ writing and reasoning skills. During those first two years of college, business students’ scores improved less than any other group’s. Communication, education and social-work majors had slightly better gains; humanities, social science, and science and engineering students saw much stronger improvement.

What accounts for those gaps? Dr. Arum and Dr. Roksa point to sheer time on task. Gains on the C.L.A. closely parallel the amount of time students reported spending on homework. Another explanation is the heavy prevalence of group assignments in business courses: the more time students spent studying in groups, the weaker their gains in the kinds of skills the C.L.A. measures.

Group assignments are a staple of management and marketing education.

For the full story, see:

DAVID GLENN. “The Default Major: Skating The B-School Blahs; Where’s the Rigor? Undergraduate Business Has an Image Problem.” The New York Times, Educational Life Section (Sun., April 17, 2011): 16-19.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the review is dated April 14, 2011 and has the title “The Default Major: Skating Through B-School.”)

The book mentioned above is:

Arum, Richard, and Josipa Roksa. Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.