Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. B2) It’s tempting to think of an economic expansion as being like a life span. The older you get, the closer you are to death; a 95-year-old probably has fewer years left to live than a 60-year-old. But this year Glenn D. Rudebusch, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, looked at the evidence from post-World War II United States economic expansions, and did not find that pattern held up at all.

“A long recovery appears no more likely to end than a short one,” Mr. Rudebusch wrote. “Like Peter Pan, recoveries appear to never grow old.”

Expansions don’t die of old age. They die because something specific killed them. It can be a wrong-footed central bank, the popping of a financial bubble or a shock from overseas. But age itself isn’t the problem.

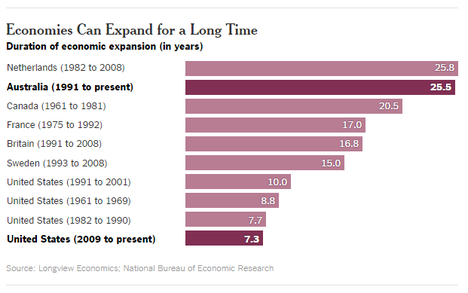

A look around the world also shows plenty of examples of expansions that have lasted a lot longer than either the seven years the current United States expansion has been underway or the longest expansion in American history, from 1991 to 2001.

Britain had a nearly 17-year expansion from the early 1990s until the 2008 global financial crisis. France had a slightly longer expansion that ended in 1992. And the record-holders among advanced economies in modern times, according to the research firm Longview Economics, are the Netherlands, which experienced a nearly 26-year “Dutch miracle” that ended in 2008, and Australia, which has an expansion that began in 1991 and is on track to overtake the Dutch soon for the longest on record.

For the full story, see:

(Note: the online version of the article has the date Oct. 27, 2016, and has the title “Will the Next President Face a Recession? Don’t Assume So.”)

Rudebusch’s research, mentioned above, appeared in: