(p. B1) The most prominent face of capitalism — Warren Buffett, the avuncular founder of Berkshire and the fourth wealthiest person in the world, worth some $89 billion — appeared to distance himself from many of his peers, who have been apologizing for capitalism of late.

“I’m a card-carrying capitalist,” Mr. Buffett said. “I believe (p. B3) we wouldn’t be sitting here except for the market system,” he added, extolling the state of the economy. “I don’t think the country will go into socialism in 2020 or 2040 or 2060.”

There is something oddly refreshing about Mr. Buffett’s frankness.

. . .

Mr. Buffett’s moral code is one of being direct, even when it is not politically correct. In his plain-spoken way, Mr. Buffett, a longtime Democrat, acknowledged that the goal of capitalism was “to be more productive all the time, which means turning out the same number of goods with fewer people or churning out more goods, with the same number,” he said.

“That is capitalism.” Two years ago at the same meeting, he bluntly said, “I’m afraid a capitalist system will always hurt some people.”

. . .

. . . at his core, he believes that the pursuit of capitalism is fundamentally moral — that it creates and produces prosperity and progress even when there are immoral actors and even when it creates inequality.

. . .

One prominent chief executive I spoke with after the meeting said he wished he could speak as bluntly as Mr. Buffett. He said in this politically sensitive climate, he often has to tiptoe around controversial topics and at least nod at the societal concern of the moment.

Therein lies the truth of the particular moment that the business community faces and one that, at least so far, Mr. Buffett, at age 88, may be immune from.

And so while Mr. Buffett may have missed an opportunity to use his perch, he comes to his views of a just business world honestly.

For the full commentary, see:

Andrew Ross Sorkin. “Buffett Still Champions Capitalism.” The New York Times (Monday, May 6, 2019): B1 & B3.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the commentary has the date May 5, 2019, and has the title “Warren Buffett’s Case for Capitalism.”)

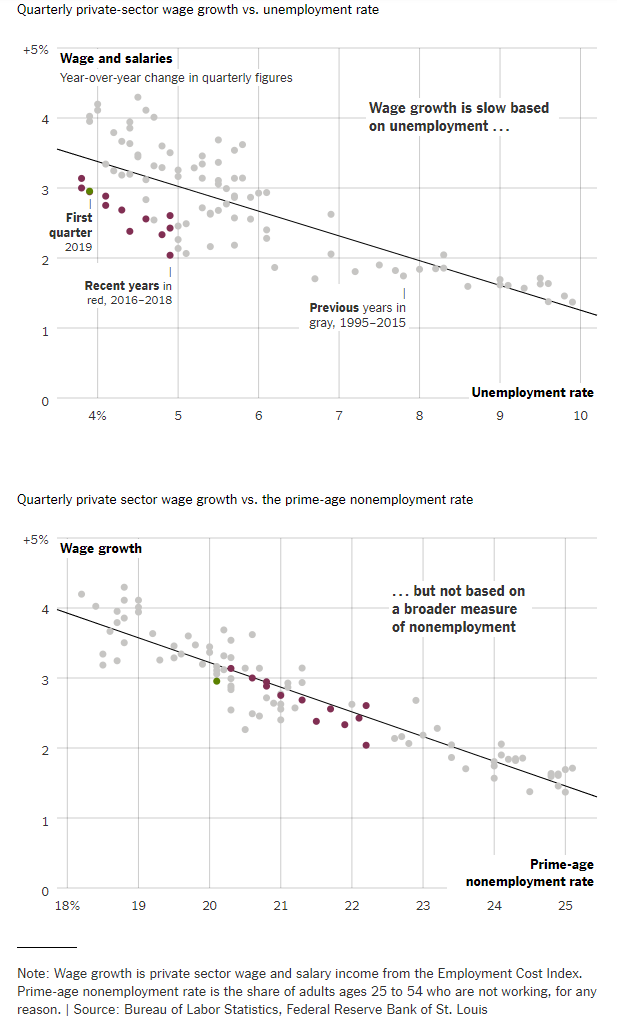

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.