The icebreaker Healy finished a new survey of the seafloor off the northern coast of Alaska. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

The icebreaker Healy finished a new survey of the seafloor off the northern coast of Alaska. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. A16) A new survey by American oceanographers of the seafloor north of Alaska, completed last month aboard the Coast Guard icebreaker Healy, provides fresh evidence that the United States has much at stake in the region. The sonar studies found hints that thousands of square miles of additional seafloor could potentially be under American control. That floor might yield important deposits of oil, gas or minerals in coming decades, government studies have concluded.

So far did the sea ice pull back this summer that the expedition was able to scan the bottom several hundred miles farther north than in previous surveys, said the project’s director, Larry Mayer, an oceanographer at the University of New Hampshire. The team found long sloping extensions 200 miles beyond previous estimates.

Though more surveys will be needed to firm up any American claim, countries have a right to expand their control of seabed resources well beyond the continental shelves bordering their coasts if they can find such sloping extensions.

For the full story, see:

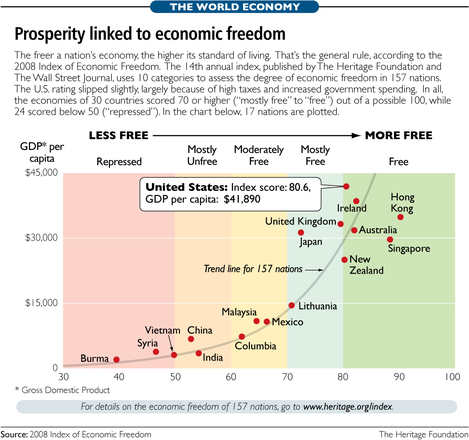

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

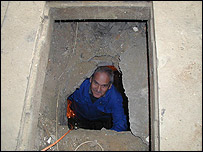

"The bolt hole was designed to hide from angry textile workers." Source of caption and photo: the BBC article quoted and cited below, and viewable at

"The bolt hole was designed to hide from angry textile workers." Source of caption and photo: the BBC article quoted and cited below, and viewable at

Source of table: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

Source of table: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above. Source of the cartoon: online version of the NYT commentary cited below.

Source of the cartoon: online version of the NYT commentary cited below. Dr. Terence Kealey is currently Vice-Chancellor at England’s only private university, the University of Buckingham. Source of photo:

Dr. Terence Kealey is currently Vice-Chancellor at England’s only private university, the University of Buckingham. Source of photo:

Source of book image:

Source of book image: