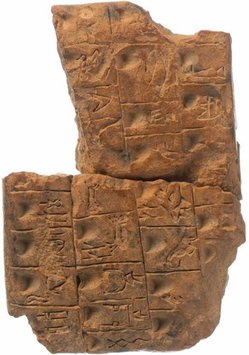

“The Vindija cave in Croatia where three small Neanderthal bones were found.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

“The Vindija cave in Croatia where three small Neanderthal bones were found.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

(p. A3) The burly Ice Age hunters known as Neanderthals, a long-extinct species, survive today in the genes of almost everyone outside Africa, according to an international research team who offer the first molecular evidence that early humans mated and produced children in liaisons with Neanderthals.

In a significant advance, the researchers mapped most of the Neanderthal genome–the first time that the heredity of such an ancient human species has been reliably reconstructed. The researchers, able for the first time to compare the relatively complete genetic coding of modern and prehistoric human species, found the Neanderthal legacy accounts for up to 4% of the human genome among people in much of the world today.

By comparing the Neanderthal genetic information to the modern human genome, the scientists were able to home in on hints of subtle differences between the ancient and modern DNA affecting skin, stature, fertility and brain power that may have given Homo sapiens an edge over their predecessors.

“It is tantalizing to think that the Neanderthal is not totally extinct,” said geneticist Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, who pioneered the $3.8 million research project. “A bit of them lives on in us today.”

. . .

For their analysis, Dr. Pääbo and his colleagues extracted DNA mostly from the fossil remains of three Neanderthal women who lived and died in Croatia between 38,000 and 45,000 years ago. From thimblefuls of powdered bone, the researchers pieced together about three billion base pairs of DNA, covering about two-thirds of the Neanderthal genome. The researchers checked those samples against fragments of genetic code extracted from three other Neanderthal specimens.

“It is a tour de force to get a genome’s worth,” said genetic database expert Ewan Birney at the European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge, England.

In research published Thursday in Science, the researchers compared the Neanderthal DNA to the genomes drawn from five people from around the world: a San tribesman from South Africa; a Yoruba from West Africa; a Han Chinese; a West European; and a Pacific islander from Papua, New Guinea. They also checked it against the recently published genome of bio-entrepreneur Craig Venter. Traces of Neanderthal heredity turned up in all but the two African representatives.

For the full story, see:

ROBERT LEE HOTZ. “Most People Carry Neanderthal Genes; Team Finds up to 4% of Human Genome Comes From Extinct Species, the First Evidence It Mated With Homo Sapiens.” The Wall Street Journal (Fri., MAY 7, 2010): A3.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the review is dated MAY 6, 2010.)

A related article, the online version of which is the source for the caption and photo above, is:

NICHOLAS WADE. “Analysis of Neanderthal Genome Points to Interbreeding with Modern Humans.” The New York Times (Fri., May 7, 2010): A9.

(Note: the online version of the review is dated May 6, 2010 and has the title “Signs of Neanderthals Mating With Humans.”)

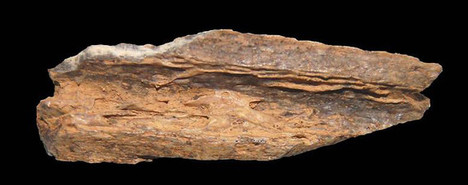

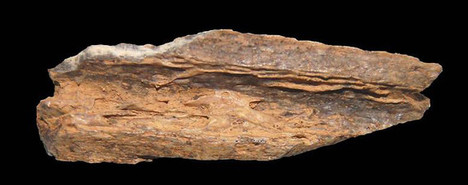

“A close-up of the bone Vindija 33.16 from Vindija cave, Croatia.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

“A close-up of the bone Vindija 33.16 from Vindija cave, Croatia.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

“Skull-cups found in Somerset, England, were worked with flint tools 14,700 years ago.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Skull-cups found in Somerset, England, were worked with flint tools 14,700 years ago.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.