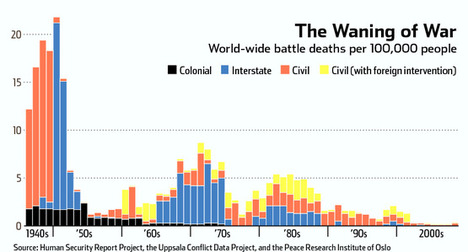

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

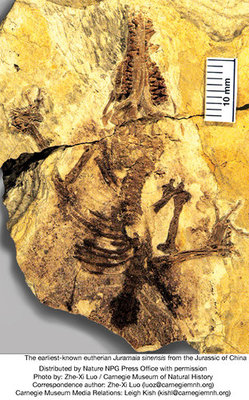

(p. C1) For centuries, social theorists like Hobbes and Rousseau speculated from their armchairs about what life was like in a “state of nature.” Nowadays we can do better. Forensic archeology–a kind of “CSI: Paleolithic”–can estimate rates of violence from the proportion of skeletons in ancient sites with bashed-in skulls, decapitations or arrowheads embedded in bones. And ethnographers can tally the causes of death in tribal peoples that have recently lived outside of state control.

These investigations show that, on average, about 15% of people in prestate eras died violently, compared to about 3% of the citizens of the earliest states. Tribal violence commonly subsides when a state or empire imposes control over a territory, leading to the various “paxes” (Romana, Islamica, Brittanica and so on) that are familiar to readers of history.

It’s not that the first kings had a benevolent interest in the welfare of their citizens. Just as a farmer tries to prevent his livestock from killing one another, so a ruler will try to keep his subjects from cycles of raiding and feuding. From his point of view, such squabbling is a dead loss–forgone opportunities to extract taxes, tributes, soldiers and slaves.

. . .

(p. C2) We see evidence of the pacifying effects of government in the way that rates of killing declined following the expansion and consolidation of states in tribal societies and in medieval Europe. And we can watch the movie in reverse when violence erupts in zones of anarchy, such as the Wild West, failed states and neighborhoods controlled by mafias and street gangs, who can’t call 911 or file a lawsuit to resolve their disputes but have to administer their own rough justice.

Another pacifying force has been commerce, a game in which everybody can win. As technological progress allows the exchange of goods and ideas over longer distances and among larger groups of trading partners, other people become more valuable alive than dead. They switch from being targets of demonization and dehumanization to potential partners in reciprocal altruism.

For example, though the relationship today between America and China is far from warm, we are unlikely to declare war on them or vice versa. Morality aside, they make too much of our stuff, and we owe them too much money.

A third peacemaker has been cosmopolitanism–the expansion of people’s parochial little worlds through literacy, mobility, education, science, history, journalism and mass media. These forms of virtual reality can prompt people to take the perspective of people unlike themselves and to expand their circle of sympathy to embrace them.

For the full essay, see:

STEVEN PINKER. “Violence Vanquished; We believe our world is riddled with terror and war, but we may be living in the most peaceable era in human existence. Why brutality is declining and empathy is on the rise.” The New York Times (Weds., SEPTEMBER 24, 2011): C1-C2.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

The article quoted was adapted by Pinker from his book:

Pinker, Steven. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. New York: Viking Press, 2011.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.