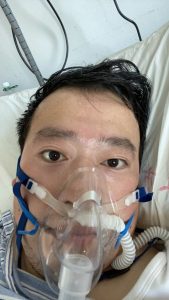

(p. B1) The Chinese public has staged what amounts to an online revolt after the death of a doctor, Li Wenliang, who tried to warn of a mysterious virus that has since killed hundreds of people in China, infected tens of thousands and forced the government to corral many of the country’s 1.4 billion people.

. . .

For many people in China, the doctor’s death shook loose pent-up anger and frustration at how the government mishandled the situation by not sharing information earlier and by silencing whistle-blowers. It also seemed, to those online, that the government hadn’t learned lessons from previous crises, continuing to quash online criticism and investigative reports that provide vital information.

Some users of Weibo, China’s Twitter-like social media platform, are saying the doctor’s death resonated because he was an ordinary person who was forced to admit to wrongdoing for doing the right thing.

Dr. Li was reprimanded by the police after he shared concerns about the virus in a social messaging app with medical school classmates on Dec. 30 [2019].

Three days later, the police compelled him to sign a statement that his warning constituted “illegal behavior.”

The doctor eventually went public with his experiences and gave interviews to help the public better understand the unfolding epidemic. (The New York Times interviewed Dr. Li days before his death.)

“He didn’t want to become a hero, but for those of us in 2020, he had reached the upper limit of what we can imagine a hero would do,” one Weibo post read. The post is one of many that users say they wrote out of shame and guilt for not standing up to an authoritarian government, as Dr. Li did.

. . .

The grief was so widespread that it appeared in unlikely corners.

“Refusing to listen to your ‘whistling,’ your country has stopped ticking, and your heart has stopped beating,” Hong Bing, the Shanghai bureau chief of the Communist Party’s official newspaper, People’s Daily, wrote on her timeline on WeChat, an instant-messaging platform. “How big a price do we have to pay to make you and your whistling sound louder, to reach every corner of the East?”

Both the Chinese- and English-language Twitter accounts of People’s Daily tweeted that Dr. Li’s death had prompted “national grief.” Both accounts deleted those messages before replacing them with more neutral, official-sounding posts.

. . .

Wang Gaofei, the chief executive of Weibo, which carries out many of the orders passed down from China’s censors, pondered what lessons China should learn from Dr. Li’s death.

“We should be more tolerant of people who post ‘untruthful information’ that aren’t malicious,” he said in a post. “If we’re only allowed to speak what we can guarantee is fact, we’re going to pay prices.”

. . .

“R.I.P. our hero,” Fan Bao, a prominent tech investor, posted on his WeChat timeline.

. . .

The hashtag #wewantfreedomofspeech# was created on Weibo at 2 a.m. on Friday [February 7, 2020] and had over two million views and over 5,500 posts by 7 a.m. It was deleted by censors, along with related topics, such as ones saying the Wuhan government owed Dr. Li an apology.

“I love my country deeply,” read one post under that topic. “But I don’t like the current system and the ruling style of my country. It covered my eyes, my ears and my mouth.”

The writer of the post complained about not being able to gain access to the internet beyond the Great Firewall. “I’ve been holding back for a long time. I feel we’ve all been holding back for a long time. It erupted today.”

Talking about freedom of speech on the Chinese internet is taboo, even though it’s written into the Constitution. So it’s a small miracle that the freedom of speech hashtag survived for over five hours.

The country’s high-powered executives have been less blunt, but have echoed the same sentiments online.

“It’s time to reflect on the deeply rooted, stability-trumps-everything thinking that’s hurt everyone,” Wang Ran, chairman of the investment bank CEC Capital, wrote on Weibo. “We all want stability,” he asked. “Will you be more stable if you cover the others’ mouths while walking on a tightrope?

(Note: the online version of the story has the date Feb. 7, 2020, and has the title “Widespread Outcry in China Over Death of Coronavirus Doctor.”)