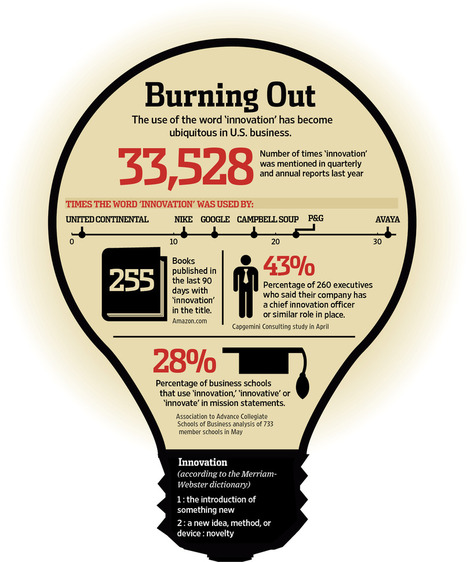

“Schumpeter” is now a verb!

(p. v) In the mid-twentieth century Joseph Schumpeter, the noted Austrian economist, popularized the term “creative destruction” to denote transformation that accompanies radical innovation. In recent years, our world has been “Schumpetered.” By virtue of the intensive infiltration of digital devices into our daily lives, we have radically altered how we communicate with one another and with our entire social network at once. We can rapidly turn to our prosthetic brain, the search engine, at any moment to find information or compensate for a senior moment. Everywhere we go we take pictures and videos with our cell phone, the one precious object that never leaves our side. Can we even remember the old days of getting film developed? No longer is there such a thing as a record album that we buy as a whole–instead we just pick the song or songs we want and download them anytime and anywhere. Forget about going to a video store to rent a movie and finding out it is not in stock. Just download it at home and watch it on television, a computer monitor, a tablet, or even your phone. If we’re not interested in getting a newspaper delivered and accumulating enormous loads of paper to recycle, or having our hands smudged by newsprint, we can simply click to pick the stories that interest us. Even clicking is starting to get old, since we can just tap a tablet or cell phone in virtual silence. The Web lets us sample nearly all books in print without even making a purchase and efficiently download the whole book in a flash. We have both a digital, virtual identity and a real one. This profile just scratches the surface of the way our lives have been radically transformed through digital innovation. Radically transformed. Creatively destroyed.

Source:

Topol, Eric. The Creative Destruction of Medicine: How the Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care. New York: Basic Books, 2012.