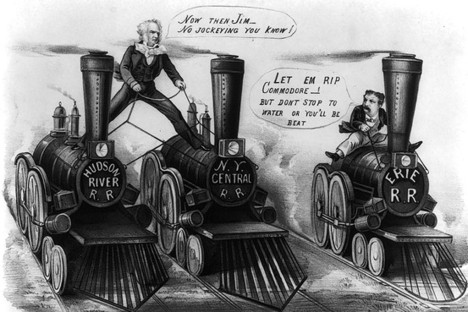

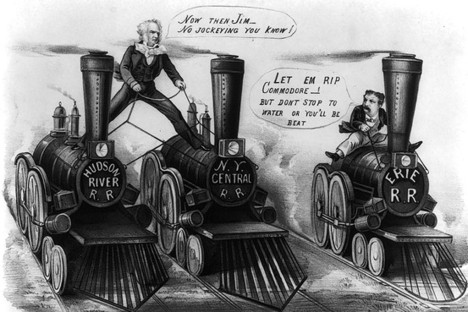

“Rails to riches: An 1870 cartoon depicting James Fisk’s attempt to stop Cornelius Vanderbilt from gaining control of the Erie Railroad Company.” Source of caption and cartoon: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

“Rails to riches: An 1870 cartoon depicting James Fisk’s attempt to stop Cornelius Vanderbilt from gaining control of the Erie Railroad Company.” Source of caption and cartoon: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

I have read H.W. Brands’ Masters of Enterprise book and found that it contained some interesting anecdotes, but not very insightful interpretation. From Amity Shlaes’ useful review quoted below, I would expect the same from Brands’ most recent book.

(p. C7) Mr. Brands laments that capitalism’s triumph in the late 19th century created a disparity between the “wealthy class” and the common man that dwarfs any difference of income in our modern distribution tables. But this pitting of capitalism against democracy will not hold. When the word “class” crops up in economic discussions, watch out: it implies a perception of society held in thrall to a static economy of rigid social tiers. Capitalism might indeed preclude democracy if capitalism meant that rich people really were a permanent class, always able to keep the money they amass and collect an ever greater share. But Americans are an unruly bunch and do not stay in their classes. The lesson of the late 19th century is that genuine capitalism is a force of creative destruction, just as Joseph Schumpeter later recognized. Snapshots of rich versus poor cannot capture the more important dynamic, which occurs over time.

One capitalist idea (the railroad, say) brutally supplants another (the shipping canal). Within a few generations–and in thoroughly democratic fashion–this supplanting knocks some families out of the top tier and elevates others to it. Some poor families vault to the middle class, others drop out. If Mr. Brands were right, and the “triumph of capitalism” had deadened democracy and created a permanent overclass, Forbes’s 2010 list of billionaires would today be populated by Rockefellers, Morgans and Carnegies. The main legacy of titans, former or current, is that the innovations they support will produce social benefits, from the steel-making to the Internet.

The second failing of “Colossus” is its perpetuation of the robber-baron myth. Years ago, historian Burton Folsom noted the difference between what he labeled political entrepreneurs and market entrepreneurs. The political entrepreneur tends to compete over finite assets–or even to steal them–and therefore deserves the “robber baron” moniker. An example that Mr. Folsom provided: the ferry magnate Robert Fulton, who operated successfully on the Hudson thanks to a 30-year exclusive concession from the New York state legislature. Russia’s petrocrats nowadays enjoy similar protections. Neither Fulton nor the petrocrats qualify as true capitalists.

Market entrepreneurs, by contrast, vanquish the competition by overtaking it. On some days Cornelius Vanderbilt was a political entrepreneur–perhaps when he ruined those traitorous partners, for instance. But most days Vanderbilt typified the market entrepreneur, ruining Fulton’s monopoly in the 1820s with lower fares, the innovative and cost-saving tubular boiler and a splendid advertising logo: “New Jersey Must Be Free.” With market entrepreneurship, a third party also wins: the consumer. Market entrepreneurs are not true robbers, for their ruining serves the common good.

For the full review, see:

AMITY SHLAES. “An Age of Creative Destruction.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., October 16, 2010): C7.

(Note: the online version of the article is dated October 29 (sic), 2010.)

The book under critical review by Shlaes:

Brands, H.W. American Colossus: The Triumph of Capitalism, 1865-1900. New York: Doubleday, 2010.

The Folsom book rightly praised in passing by Shlaes is:

Folsom, Burton W. The Myth of the Robber Barons. 4th ed: Young America’s Foundation, 2003.