“Sebastian Thrun, a research professor at Stanford, is Udacity’s chief executive officer.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Sebastian Thrun, a research professor at Stanford, is Udacity’s chief executive officer.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. A1) SAN JOSE, Calif. — Dazzled by the potential of free online college classes, educators are now turning to the gritty task of harnessing online materials to meet the toughest challenges in American higher education: giving more students access to college, and helping them graduate on time.

. . .

Here at San Jose State, . . . , two pilot programs weave material from the online classes into the instructional mix and allow students to earn credit for them.

“We’re in Silicon Valley, we (p. A3) breathe that entrepreneurial air, so it makes sense that we are the first university to try this,” said Mohammad Qayoumi, the university’s president. “In academia, people are scared to fail, but we know that innovation always comes with the possibility of failure. And if it doesn’t work the first time, we’ll figure out what went wrong and do better.”

. . .

Dr. Qayoumi favors the blended model for upper-level courses, but fully online courses like Udacity’s for lower-level classes, which could be expanded to serve many more students at low cost. Traditional teaching will be disappearing in five to seven years, he predicts, as more professors come to realize that lectures are not the best route to student engagement, and cash-strapped universities continue to seek cheaper instruction.

“There may still be face-to-face classes, but they would not be in lecture halls,” he said. “And they will have not only course material developed by the instructor, but MOOC materials and labs, and content from public broadcasting or corporate sources. But just as faculty currently decide what textbook to use, they will still have the autonomy to choose what materials to include.”

. . .

Any wholesale online expansion raises the specter of professors being laid off, turned into glorified teaching assistants or relegated to second-tier status, with only academic stars giving the lectures. Indeed, the faculty unions at all three California higher education systems oppose the legislation requiring credit for MOOCs for students shut out of on-campus classes.

. . .

“Our ego always runs ahead of us, making us think we can do it better than anyone else in the world,” Dr. Ghadiri said. “But why should we invent the wheel 10,000 times? This is M.I.T., No. 1 school in the nation — why would we not want to use their material?”

There are, he said, two ways of thinking about what the MOOC revolution portends: “One is me, me, me — me comes first. The other is, we are not in this business for ourselves, we are here to educate students.”

For the full story, see:

TAMAR LEWIN. “Colleges Adapt Online Courses to Ease Burden.” The New York Times (Tues., April 30, 2013): A1 & A3.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date April 29, 2013.)

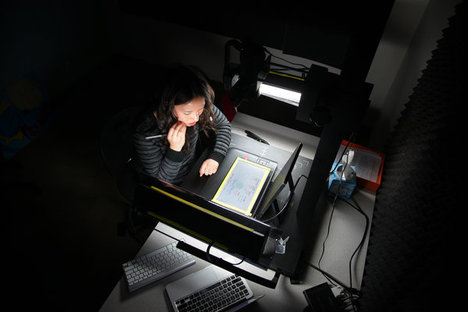

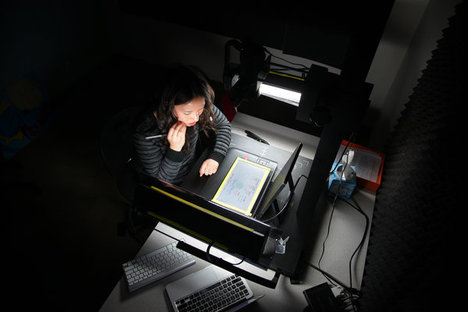

“Katie Kormanik preparing to record a statistics course at Udacity, an online classroom instruction provider in Mountain View, Calif.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Katie Kormanik preparing to record a statistics course at Udacity, an online classroom instruction provider in Mountain View, Calif.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.