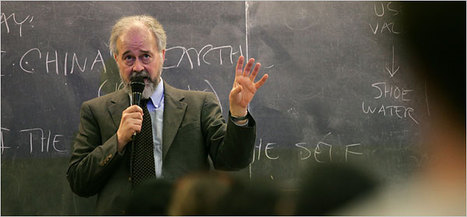

Professor William C. Dowling. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Professor William C. Dowling. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. C15) For more than a decade at Rutgers, Dr. Dowling has stood as an idealistic absolutist, an intellectual convinced that the thunder of big-time athletics was crumbling the ivory tower of academe.

He has been the conscience, the Cassandra, the crank, the nag, the pain, infuriating opponents and, at times, exasperating allies. Enough years of being the whistle-blower, after all, can make even a tuneful musician sound shrill.

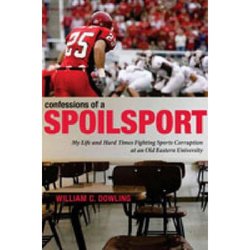

But now, just as Rutgers’s recent triumphs in football and basketball might seem to have justified the university’s investment of tens of millions of dollars, Dr. Dowling has answered in his own subversive way. His memoir of the decade-long campaign against high-stakes athletics at Rutgers, “Confessions of a Spoilsport,” has just been published by Penn State University Press. It is his valediction, and its tone, far from mournful, is defiant.

“I wanted this book to be a monument,” Dr. Dowling, 62, said after class. “I wanted it to be a monument to the kids and the faculty who rallied around this issue. We tried to take on the monster of commercialized sports, even if it swallowed us up and passed us out the other end. Someone should know that we fought the good fight. And because I believe in literature as a form of symbolic action, I want readers to see the possibility of another way. Think about the impact of a book like ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ on slavery.”

. . .

Dartmouth . . . instilled in Dr. Dowling an appreciation for what he calls now “participatory sports” — sports without scholarships, separate dorms, team tutors, product endorsements, television contracts, reduced admissions standards, easy classes and so many other tropes of Division I-A sports.

Rutgers, in turn, provided a striking example of before and after. For more than 100 years after playing Princeton in the first intercollegiate football game in 1869, Rutgers had competed against schools like Lafayette and Colgate with which it shared academic standards. Then, in 1991, Rutgers joined the Big East Conference, making it a peer of ethically challenged football factories like Miami.

Dr. Dowling grew convinced that the shift was degrading the caliber of students, indeed the entire communal culture. . . . And while he enjoyed teaching many members of the track, swimming and crew teams in his courses, he vociferously resisted the notion that athletic scholarships offered opportunity to low-income, minority students.

“If you were giving the scholarship to an intellectually brilliant kid who happens to play a sport, that’s fine,” he said. “But they give it to a functional illiterate who can’t read a cereal box, and then make him spend 50 hours a week on physical skills. That’s not opportunity. If you want to give financial help to minorities, go find the ones who are at the library after school.”

For the full story, see:

SAMUEL G. FREEDMAN. "EDUCATION; To the Victors at Rutgers Also Goes the ‘Spoilsport’." The New York Times (Weds., September 26, 2007): C15.

(Note: ellipses added.)

Here is the description of Dowling’s book that appears on Amazon:

"Universities exist to transmit understanding and ideals and values to students . . . not to provide entertainment for spectators or employment for athletes. . . . When I entered a much smaller Rutgers sixty years ago, athletics were an important but strictly minor aspect of Rutgers education. I trust that today’s much larger Rutgers will honor this tradition from which I benefited so much." –Milton Friedman, Rutgers ’32, Nobel Prize in Economics, 1976

In 1998, Milton Friedman’s statement drew national attention to Rutgers 1000, a campaign in which students, faculty, and alumni were resisting the takeover of their university by commercialized Division IA athletics. Subsequently, the movement received extensive coverage in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Chronicle of Higher Education, Sports Illustrated, and other publications.

Today, "big-time" college athletics remains a hotly debated issue at Rutgers. Why did an old eastern university that had long competed against such institutions as Colgate, Columbia, Lafayette, and Princeton, choose, by joining the Big East conference in 1994, to plunge into the world of such TV-revenue-driven extravaganzas as "March Madness" and the Tostitos Fiesta Bowl? What is the moral for universities where big-time college sports have already become the primary source of institutional identity?

Confessions of a Spoilsport is the story of an English professor who, having seen the University of New Mexico sink academically in the period of a major basketball scandal, was galvanized into action when Rutgers joined the Big East. It is also the story of the Rutgers 1000 students and alumni who set out against enormous odds to resist the decline of their university–eviscerated academic programs, cancellation of minor sports, loss of the "best and brightest" in-state students to the nearby College of New Jersey–while tens of millions of dollars were being lavished on Division IA athletics. Ultimately, however, the story of Rutgers 1000 is what the New York Times called it when Milton Friedman issued his ringing statement: a struggle for the soul of a major university.

The reference to Dowling’s book, is:

Dowling, William C. Confessions of a Spoilsport: My Life and Hard Times Fighting Sports Corruption at an Old Eastern University. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007.

Source of book image: http://www.amazon.com/Confessions-Spoilsport-Fighting-Corruption-University/dp/0271032936/ref=pd_bbs_sr_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1196229303&sr=1-1

Source of book image: http://www.amazon.com/Confessions-Spoilsport-Fighting-Corruption-University/dp/0271032936/ref=pd_bbs_sr_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1196229303&sr=1-1

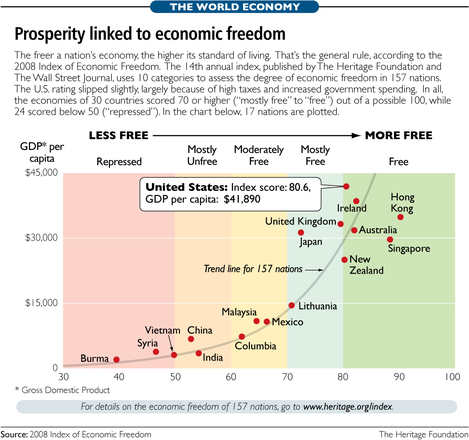

Source of graph: http://www.heritage.org/Press/ALAChart/images/ALC_017_index_econ_freedom_3col_c.jpg

Source of graph: http://www.heritage.org/Press/ALAChart/images/ALC_017_index_econ_freedom_3col_c.jpg  Source of table: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

Source of table: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

Source of the cartoon: online version of the NYT commentary cited below.

Source of the cartoon: online version of the NYT commentary cited below. "Thor Halvorssen at his office in the Empire State Building." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

"Thor Halvorssen at his office in the Empire State Building." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Columnist Bob Herbert. Source of photo: online version of the NYT column quoted and cited above.

Columnist Bob Herbert. Source of photo: online version of the NYT column quoted and cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.