Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

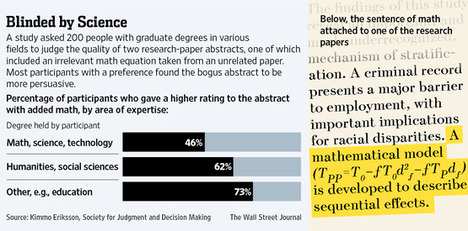

(p. A2) . . . research has shown that even those who should be especially clear-sighted about numbers–scientific researchers, for example, and those who review their work for publication–are often uncomfortable with, and credulous about, mathematical material. As a result, some research that finds its way into respected journals–and ends up being reported in the popular press–is flawed.

In the latest study, Kimmo Eriksson, a mathematician and researcher of social psychology at Sweden’s Mälardalen University, chose two abstracts from papers published in research journals, one in evolutionary anthropology and one in sociology. He gave them to 200 people to rate for quality–with one twist. At random, one of the two abstracts received an additional sentence, the one above with the math equation, which he pulled from an unrelated paper in psychology. The study’s 200 participants all had master’s or doctoral degrees. Those with degrees in math, science or technology rated the abstract with the tacked-on sentence as slightly lower-quality than the other. But participants with degrees in humanities, social science or other fields preferred the one with the bogus math, with some rating it much more highly on a scale of 0 to 100.

“Math makes a research paper look solid, but the real science lies not in math but in trying one’s utmost to understand the real workings of the world,” Prof. Eriksson said.

For the full story, see:

CARL BIALIK. “THE NUMBERS GUY; Don’t Let Math Pull the Wool Over Your Eyes.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., January 5, 2013): A2.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date January 4, 2013,)

A pdf of Eriksson’s published article can be downloaded from:

Eriksson, Kimmo. “The Nonsense Math Effect.” Judgment and Decision Making 7, no. 6 (November 2012): 746-49.