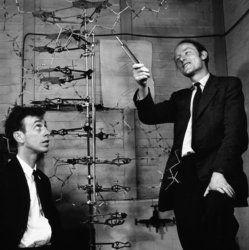

“Partners; James D. Watson, left, with Francis Crick and their model of part of a DNA molecule in 1953. Crick did not like Dr. Watson’s book at first.” Source of caption: print version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. D2) Anyone seeking to understand modern biology and genomics could do much worse than start with the discovery of the structure of DNA, on which almost everything else is based. The classic account of the discovery, “The Double Helix,” by James D. Watson, was first published in 1968 and has now been reissued in an annotated and illustrated edition.

. . .

An appendix makes it clear how close “The Double Helix” came to being suppressed. Dr. Watson sent the manuscript to many of the central players, inviting their comments on its accuracy. Harvard University Press had accepted it for publication, but the Harvard authorities came to feel it was too hot a potato and dropped it.

Atheneum Publishers, which picked it up, requested a blander title — previous versions had included “Honest Jim” and “Base Pairs.” The latter — referring to the paired sets of chemical bases that form the steps in the double helix, and by extension to the two discoverers — gave particular offense to Crick, who failed to see why he should be considered base. Atheneum’s lawyers then tried to make the text inoffensive to the many possible litigants.

But Dr. Watson was able to resist many changes. He had cannily persuaded Bragg to write a foreword, and this endorsement from an establishment figure provided sufficient protection for the book to be published. It proceeded to sell more than a million copies.

For the full review, see:

NICHOLAS WADE. “BOOKS ON SCIENCE; Twists in the Tale of the Great DNA Discovery.” The New York Times (Tues., November 13, 2012): D2.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date November 12, 2012.)

The annotated version of the Watson book is:

Watson, James D. The Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012.