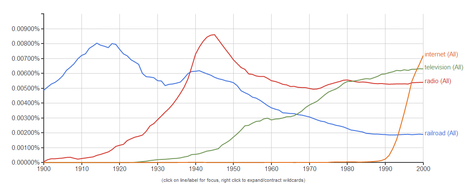

I used Google’s Ngram tool to generate the Ngram above, using the same technologies used in the Ngram that appeared in the print (but not the online) version of the article quoted and cited below. The blue line is “railroad”; the red line is “radio”; the green line is “television”; the orange line is “internet.” The search was case-insensitive. The print (but not the online) version of the article quoted and cited below, includes a caption that describes the Ngram tool: “A Google tool, the Ngram Viewer, allows anyone to chart the use of words and phrases in millions of books back to the year 1500. By measuring historical shifts in language, the tool offers a quantitative approach to understanding human history.”

I used Google’s Ngram tool to generate the Ngram above, using the same technologies used in the Ngram that appeared in the print (but not the online) version of the article quoted and cited below. The blue line is “railroad”; the red line is “radio”; the green line is “television”; the orange line is “internet.” The search was case-insensitive. The print (but not the online) version of the article quoted and cited below, includes a caption that describes the Ngram tool: “A Google tool, the Ngram Viewer, allows anyone to chart the use of words and phrases in millions of books back to the year 1500. By measuring historical shifts in language, the tool offers a quantitative approach to understanding human history.”

(p. 3) Today, the Ngram Viewer contains words taken from about 7.5 million books, representing an estimated 6 percent of all books ever published. Academic researchers can tap into the data to conduct rigorous studies of linguistic shifts across decades or centuries. . . .

The system can also conduct quantitative checks on popular perceptions.

Consider our current notion that we live in a time when technology is evolving faster than ever. Mr. Aiden and Mr. Michel tested this belief by comparing the dates of invention of 147 technologies with the rates at which those innovations spread through English texts. They found that early 19th-century inventions, for instance, took 65 years to begin making a cultural impact, while turn-of-the-20th-century innovations took only 26 years. Their conclusion: the time it takes for society to learn about an invention has been shrinking by about 2.5 years every decade.

“You see it very quantitatively, going back centuries, the increasing speed with which technology is adopted,” Mr. Aiden says.

Still, they caution armchair linguists that the Ngram Viewer is a scientific tool whose results can be misinterpreted.

Witness a simple two-gram query for “fax machine.” Their book describes how the fax seems to pop up, “almost instantaneously, in the 1980s, soaring immediately to peak popularity.” But the machine was actually invented in the 1840s, the book reports. Back then it was called the “telefax.”

Certain concepts may persevere, even as the names for technologies change to suit the lexicon of their time.

For the full story, see:

NATASHA SINGER. “TECHNOPHORIA; In a Scoreboard of Words, a Cultural Guide.” The New York Times, SundayBusiness Section (Sun., December 8, 2013): 3.

(Note: ellipsis added; bold in original.)

(Note: the online version of the article has the date December 7, 2013.)