Graphic on optimal savings. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Graphic on optimal savings. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Could it be possible that you are saving too much for your retirement?

. . .

. . . , a small band of economists from universities, research institutions and the government are clearly expressing the blasphemy that many Americans could be saving less than they are being told to by the financial services industry — and spending more — while they are younger. The negative savings rate, they say, is wildly distorted.

According to them, the financial industry, with its ostensibly objective online calculators, overstates how much money someone will need in retirement. Some, in fact, contend that financial firms have a pointed interest in persuading people to save much more than they need because the companies earn fees on managing that money.

The more realistic amount could be as little as half the typical recommendation made by Fidelity, Vanguard or any number of other financial institutions.

For a middle-income couple, that could mean trading $400,000 in retirement money for about $3,000 a year more during prime working years to spend on education or home improvement. “For a middle-class household, that’s a lot of money,” said Laurence J. Kotlikoff, a Boston University economics professor, who is on the forefront of this research into spending and savings, and is selling his own retirement calculator.

. . .

Nevertheless, the loose confederation of well-regarded economists, who have not been working in concert, say their research points to the startling conclusion that many Americans are saving too much, not too little. Indeed, their studies of the savings and spending habits of the generation born between 1931 and 1941 revealed that at least 80 percent had accumulated more than enough wealth for retirement. While they have not studied the baby boom generation as closely, they believe that the greater wealth of that generation should also leave those retirees secure.

A study last October by another group of economists, including two working for the Federal Reserve Board, found 88 percent of retirees age 51 and older had adequate wealth.

“Even the most casual reading of the popular press will have you convinced that Americans are heading like lemmings over a cliff,” said John Karl Scholz, an economics professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. “Going into this, I had no idea that we’d find any results anything like this.”

. . .

Mr. Scholz said he and his co-authors of a study, “Are Americans Saving ‘Optimally’ for Retirement?” found oversaving across all economic and education levels and most ethnic or racial groups as well. (It found that Hispanics tended to save less.) Those who were not saving enough were usually missing their target by only a small amount.

The one exception to this optimism involves people who enter retirement single, either because their spouse died early, they divorced, or they never married. The studies found this group did not save enough.

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

Drawing of Johnny Astro toy. Source of drawing: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Drawing of Johnny Astro toy. Source of drawing: online version of the NYT article cited above.

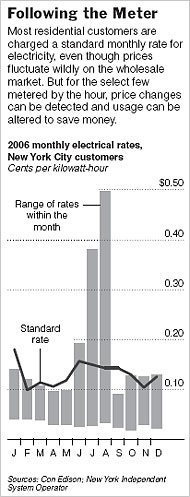

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above. Residential plastic pipe. Source of photo:

Residential plastic pipe. Source of photo:

Source of book image:

Source of book image: