Bill Gates speaking at the Davos meetings in Switzerland on January 24, 2008. Source of the photo: http://graphics8.nytimes.com/images/blogs/dealbook/davos2008/gates600.jpg

Bill Gates speaking at the Davos meetings in Switzerland on January 24, 2008. Source of the photo: http://graphics8.nytimes.com/images/blogs/dealbook/davos2008/gates600.jpg

The German scholars used to call it “Das Adam Smith Problem”: how to reconcile the Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments with his later Wealth of Nations. One alleged inconsistency is the advocacy of altruism in the former, and the advocacy of self-interest in the latter.

But a closer reading of The Theory of Moral Sentiments solves the problem. Smith thought a case could be made for altruism, but only toward those we know really well, which primarily meant one’s own family, and maybe also others in one’s community who one knows well. The reason is that altruism works only when we know very well the situation and values of those who we propose to help. Otherwise, we may end up doing more harm than good.

So when Gates embarks on global altruism, he should be careful in citing Smith for support.

The passage quoted below discusses Bill Gates’s interpretation of Adam Smith:

(p. A15) Key to Mr. Gates’s plan will be for businesses to dedicate their top people to poor issues — an approach he feels is more powerful than traditional corporate donations and volunteer work. Governments should set policies and disburse funds to create financial incentives for businesses to improve the lives of the poor, he plans to say today. “If we can spend the early decades of the 21st century finding approaches that meet the needs of the poor in ways that generate profits for business, we will have found a sustainable way to reduce poverty in the world,” Mr. Gates plans to say.

In the interview, Mr. Gates was emphatic that he’s not calling for a fundamental change in how capitalism works. He cited Adam Smith, whose treatise, “The Wealth of Nations,” lays out the rationale for the self-interest that drives capitalism and companies like Microsoft. That shouldn’t change, “one iota,” Mr. Gates said.

But there’s more to Adam Smith, he added. “This was written before ‘Wealth of Nations,'” Mr. Gates said, flipping through a copy of Adam Smith’s 1759 book, “The Theory of Moral Sentiments.” It argues that humans gain pleasure from taking an interest in the “fortunes of others.” Mr. Gates will quote from that book in his speech today.

Talk of “moral sentiments” may seem surprising from a man whose competitive drive is so fierce that it drew legal challenges from antitrust authorities. But Mr. Gates said his thinking about capitalism has been evolving for years. He outlined part of his evolution from software titan to philanthropist in a speech last June to Harvard’s graduating class, recounting how when he left Harvard in 1975 he knew little of the inequities in the world. A range of experiences including trips to Africa and India have helped raise that awareness.

In the Harvard speech, Mr. Gates floated the idea of “creative capitalism.” But at the time he had only a “fuzzy” sense of what he meant. To clarify his thinking, he decided to prepare the Davos speech.

For the full story, see:

ROBERT A. GUTH. “Bill Gates Issues Call For Kinder Capitalism; Famously Competitive, Billionaire Now Urges Business to Aid the Poor.” The Wall Street Journal (Thurs., January 24, 2008): A1 & A15.

One good article that discusses some of the issues in my initial commentary is:

Coase, Ronald H. “Adam Smith’s View of Man.” In Essays on Economics and Economists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Source of the graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.

Source of image: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

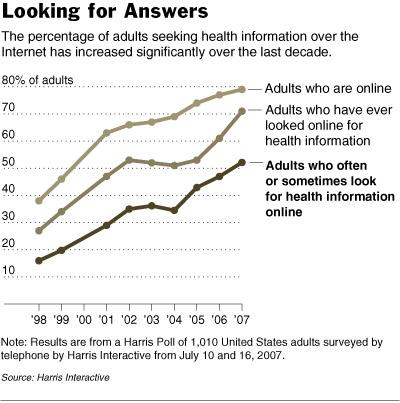

Source of image: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below. Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.