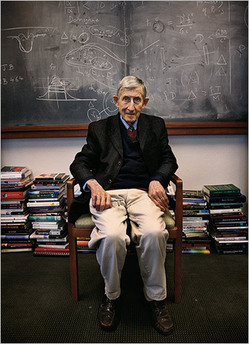

Dyson says that the “climate-studies people” have “. . . come to believe models are real and forget they are only models.” Source of photo and caption: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. (The caption used here is adapted from the body of the article, and is not the caption used under the photo in the article.)

Dyson says that the “climate-studies people” have “. . . come to believe models are real and forget they are only models.” Source of photo and caption: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below. (The caption used here is adapted from the body of the article, and is not the caption used under the photo in the article.)

The cover story of the March 29, 2009 Sunday New York Times Magazine section was a breath of fresh air on an old hot topic. Here is a small sample of a large article:

(p. 32) FOR MORE THAN HALF A CENTURY the eminent physicist Freeman Dyson has quietly resided in Princeton, N.J., on the wooded former farmland that is home to his employer, the Institute for Advanced Study, this country’s most rarefied community of scholars. Lately, however, since coming “out of the closet as far as global warming is concerned,” as Dyson sometimes puts it, there has been noise all around him. Chat rooms, Web threads, editors’ letter boxes and Dyson’s own e-mail queue resonate with a thermal current of invective in which Dyson has discovered himself variously described as “a pompous twit,” “a blowhard,” “a cesspool of misinformation,” “an old coot riding into the sunset” and, perhaps inevitably, “a mad scientist.” Dyson had proposed that whatever inflammations the climate was experiencing might be a (p. 34 sic) good thing because carbon dioxide helps plants of all kinds grow. Then he added the caveat that if CO2 levels soared too high, they could be soothed by the mass cultivation of specially bred “carbon-eating trees,” whereupon the University of Chicago law professor Eric Posner looked through the thick grove of honorary degrees Dyson has been awarded — there are 21 from universities like Georgetown, Princeton and Oxford — and suggested that “perhaps trees can also be designed so that they can give directions to lost hikers.” Dyson’s son, George, a technology historian, says his father’s views have cooled friendships, while many others have concluded that time has cost Dyson something else. There is the suspicion that, at age 85, a great scientist of the 20th century is no longer just far out, he is far gone — out of his beautiful mind.

But in the considered opinion of the neurologist Oliver Sacks, Dyson’s friend and fellow English expatriate, this is far from the case. “His mind is still so open and flexible,” Sacks says. Which makes Dyson something far more formidable than just the latest peevish right-wing climate-change denier. Dyson is a scientist whose intelligence is revered by other scientists — William Press, former deputy director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory and now a professor of computer science at the University of Texas, calls him “infinitely smart.” Dyson — a mathematics prodigy who came to this country at 23 and right away contributed seminal work to physics by unifying quantum and electrodynamic theory — not only did path-breaking science of his own; he also witnessed the development of modern physics, thinking alongside most of the luminous figures of the age, including Einstein, Richard Feynman, Niels Bohr, Enrico Fermi, Hans Bethe, Edward Teller, J. Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Witten, the “high priest of string theory” whose office at the institute is just across the hall from Dyson’s. Yet instead of hewing to that fundamental field, Dyson chose to pursue broader and more unusual pursuits than most physicists — and has lived a more original life.

. . .

(p. 36) Not long ago Dyson sat in his institute office, a chamber so neat it reminds Dyson’s friend, the writer John McPhee, of a Japanese living room. On shelves beside Dyson were books about stellar evolution, viruses, thermodynamics and terrorism. “The climate-studies people who work with models always tend to overestimate their models,” Dyson was saying. “They come to believe models are real and forget they are only models.” Dyson speaks in calm, clear tones that carry simultaneous evidence of his English childhood, the move to the United States after completing his university studies at Cambridge and more than 50 years of marriage to the German-born Imme, but his opinions can be barbed, especially when a conversation turns to climate change. Climate models, he says, take into account atmospheric motion and water levels but have no feeling for the chemistry and biology of sky, soil and trees. “The biologists have essentially been pushed aside,” he continues. “Al Gore’s just an opportunist. The person who is really responsible for this overestimate of global warming is Jim Hansen. He consistently exaggerates all the dangers.”

Dyson agrees with the prevailing view that there are rapidly rising carbon-dioxide levels in the atmosphere caused by human activity. To the planet, he suggests, the rising carbon may well be a MacGuffin, a striking yet ultimately benign occurrence in what Dyson says is still “a relatively cool period in the earth’s history.” The warming, he says, is not global but local, “making cold places warmer rather than making hot places hotter.” Far from expecting any drastic harmful consequences from these increased temperatures, he says the carbon may well be salubrious — a sign that “the climate is actually improving rather than getting worse,” because carbon acts as an ideal fertilizer promoting forest growth and crop yields. “Most of the evolution of life occurred on a planet substantially warmer than it is now,” he contends, “and substantially richer in carbon dioxide.” Dyson calls ocean acidification, which many scientists say is destroying the saltwater food chain, a genuine but probably exaggerated problem. Sea levels, he says, are rising steadily, but why this is and what dangers it might portend “cannot be predicted until we know much more about its causes.”

For the full article, see:

NICHOLAS DAWIDOFF. “The Civil Heretic.” The New York Times Magazine (Sun., March 29, 2009): 32-39, 54, 57-59.

(Note: ellipses in top photo caption, and in article quotes, are added.)

“Freeman Dyson.” Source of photo and caption: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

So some scientists “believe models are real”. I hear otherwise intelligent people saying they “believe in” one theory or another. Has science reverted to the time of Galileo? What has belief to do with science?

Karl Popper must be spinning in his grave.

ptg ( is it for poltergeist )

I gather, you superimpose inteligence to belief? Is that right? Is it conditionally or unconditionally?

Another one, science and belief are exclusive? Right? Conditionally or unconditionally?

Do you consider yourself to be a scientist?

To me you sound more like a compilation artist, in the sense of a medieval cleric scripture re-writer. And you dare to draw parallel with Galileo? Shameless!

No, you’re not an interpreter, but simply putting it a scripture maintenance worker. That is exactly the title you may get, if you coexist in the field of basic science.

Now, I will make a statement. Belief has everything to do with science, and with the process of creative thinking.

Everything.

Creative thinking and belief do not exclude each other, quite contrary.

Popper? This is what Mr. Popper says in The Logic of Scientific Discovery:

“My belief is that the resolution of conflicts between hypotheses and observations can only be a matter of the collective judgment of scientists, in each individual case.[13]”

It is not his ratio or intelligence that is telling him the above, it is his “belief”.

I think that you immaturely decided to chose sides, while the truth is elsewhere.

It is clear that abvillian is upset, but less clear exactly why, and with whom. He starts out directing his comments at ptg, but from some of his comments, I suspect that I am his main target. Many issues are briefly touched on. On one of them, my view of theories is that they are inference tools that are separate from, and secondary to, the evidence that they explain and predict. On another issue, if it is me who abvillian is identifying as a “compilation artist” and as a “medieval cleric scripture re-writer,” then I plead partly guilty. Part of what I am trying to do in many of the entries of this blog is to highlight and preserve important evidence and arguments that I believe bear on important policy decisions. I usually believe that the evidence and arguments presented are plausible and important, but I do not go so far as to view them as sacred (as would a medieval cleric of the texts he would preserve).