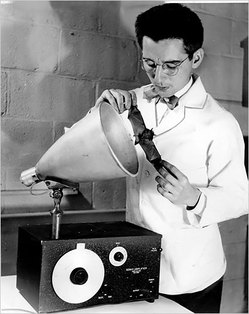

“Robert Galambos, . . . , studied the inaudible sounds that allow bats to fly in the dark.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. 20) Dr. Robert Galambos, a neuroscientist whose work included helping to prove how bats navigate in total darkness and deciphering the codes by which nerves transmit sounds to the brain, died June 18 at his home in the La Jolla section of San Diego. He was 96.

. . .

In 1960, while on an airplane, Dr. Galambos wrote that he had an inspiring thought: that the tiny cells that make up 40 percent of the brain, called glia, are as crucial to mental functioning as neurons.

“I know how the brain works!” he exclaimed to his companion.

But his superiors at Walter Reed found the theory so radical that he was soon job-hunting. The view at the time was that glia existed mainly to support neurons, considered the structural and functional unit of the nervous system. But Dr. Galambos clung to his belief, despite the failure of three experiments he performed in the 1960s.

Since then, scientific opinion has been shifting in his direction. In 2008, Ben A. Barres of the Stanford University School of Medicine wrote glowingly in the journal Neuron about the powerful role glia are now seen to play. He concluded, “Quite possibly the most important roles of glia have yet to be imagined.”

For the full obituary, see:

DOUGLAS MARTIN. “Robert Galambos, 96, Dies; Studied Nerves and Sound.” The New York Times, First Section (Sun., July 18, 2010): 20.

(Note: the online version of the article is dated July 15, 2010 and has the title “Robert Galambos, Neuroscientist Who Showed How Bats Navigate, Dies at 96.”)

(Note: ellipses added.)