Source of book image: http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1360928417l/15904345.jpg

(p. C4) If paperwork studies have an unofficial standard-bearer and theoretician, it’s Mr. Kafka. In “The Demon of Writing” he lays out a concise if eccentric intellectual history of people’s relationship with the paperwork that governs (and gums up) so many aspects of modern life. The rise of modern bureaucracy is a well-established topic in sociology and political science, where it is often related as a tale of increasing order and rationality. But the paper’s-eye view championed by Mr. Kafka tells a more chaotic story of things going wrong, or at least getting seriously messy.

It’s an idea that makes perfect sense to any modern cubicle dweller whose overflowing desk stands as a rebuke to the utopian promise of the paperless office. But Mr. Kafka traces the modern age of paperwork to the French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, which guaranteed citizens the right to request a full accounting of the government. An explosion of paper followed, along with jokes, gripes and tirades against the indignity of rule by paper-pushing clerks, a fair number of whom, judging from the stories in Mr. Kafka’s book, went mad.

For the full story, see:

JENNIFER SCHUESSLER. “The Paper Trail Through History.” The New York Times (Mon., December 17, 2012): C1 & C4.

(Note: the online version of the story has the date December 16, 2012.)

Kafka’s book, mentioned above, is:

Kafka, Ben. The Demon of Writing: Powers and Failures of Paperwork. Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books, 2012.

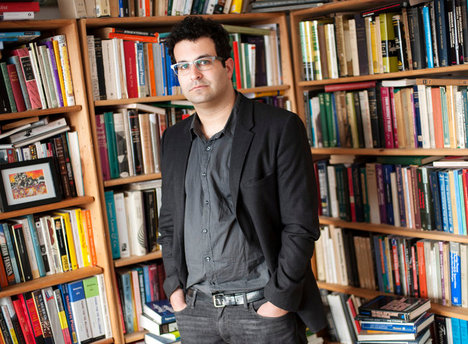

“Ben Kafka, author of “The Demon of Writing: Powers and Failures of Paperwork.”” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Ben Kafka, author of “The Demon of Writing: Powers and Failures of Paperwork.”” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.