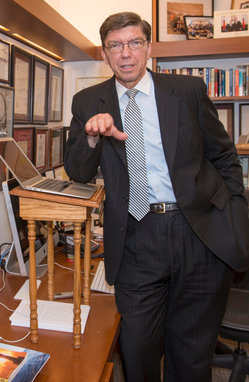

“Harvard Business School faced a choice between different models of online instruction. Prof. Michael Porter favored the development of online courses that would reflect the school’s existing strategy.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Harvard Business School faced a choice between different models of online instruction. Prof. Michael Porter favored the development of online courses that would reflect the school’s existing strategy.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. 1) Universities across the country are wrestling with the same question — call it the educator’s quandary — of whether to plunge into the rapidly growing realm of online teaching, at the risk of devaluing the on-campus education for which students pay tens of thousands of dollars, or to stand pat at the risk of being left behind.

At Harvard Business School, the pros and cons of the argument were personified by two of its most famous faculty members. For Michael Porter, widely considered the father of modern business strategy, the answer is yes — create online courses, but not in a way that undermines the school’s existing strategy. “A company must stay the course,” Professor Porter has written, “even in times of upheaval, while constantly improving and extending its distinctive positioning.”

For Clayton Christensen, whose 1997 book, “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” propelled him to academic stardom, the only way that market leaders like Harvard (p. 4) Business School survive “disruptive innovation” is by disrupting their existing businesses themselves. This is arguably what rival business schools like Stanford and the Wharton School have been doing by having professors stand in front of cameras and teach MOOCs, or massive open online courses, free of charge to anyone, anywhere in the world. For a modest investment by the school — about $20,000 to $30,000 a course — a professor can reach a million students, says Karl Ulrich, vice dean for innovation at Wharton, part of the University of Pennsylvania.

“Do it cheap and simple,” Professor Christensen says. “Get it out there.”

But Harvard Business School’s online education program is not cheap, simple, or open. It could be said that the school opted for the Porter theory.

. . .

“Harvard is going to make a lot of money,” Mr. Ulrich predicted. “They will sell a lot of seats at those courses. But those seats are very carefully designed to be off to the side. It’s designed to be not at all threatening to what they’re doing at the core of the business school.”

Exactly, warned Professor Christensen, who said he was not consulted about the project. “What they’re doing is, in my language, a sustaining innovation,” akin to Kodak introducing better film, circa 2005. “It’s not truly disruptive.”

. . .

One morning, [Harvard Business School Dean Nitin Nohria] sat down for one of his regular breakfasts with students. “Three of them had just been in Clay’s course,” which had included a case study on the future of Harvard Business School, Mr. Nohria said. “So I asked them, ‘What was the debate like, and how would you think about this?’ They, too, split very deeply.”

Some took Professor Christensen’s view that the school was a potential Blockbuster Video: a high-cost incumbent — students put the total cost of the two-year M.B.A. at around $100,0000 — that would be upended by cheaper technology if it didn’t act quickly to make its own model obsolete. At least one suggested putting the entire first-year curriculum online.

Others weren’t so sure. ” ‘This disruption is going to happen,’ ” is how Mr. Nohria described their thinking, ” ‘but it’s going to happen to a very different segment of business education, not to us.’ ” The power of Harvard’s brand, networking opportunities and classroom experience would protect it from the fate of second- and third-tier schools, a view that even Professor Christensen endorses — up to a point.

“We’re at the very high end of the market, and disruption always hits the high end last,” said Professor Christensen, who recently predicted that half of the United States’ universities could face bankruptcy within 15 years.

For the full story, see:

JERRY USEEM. “B-School, Disrupted.” The New York Times, SundayBusiness Section (Sun., June 1, 2014): 1 & 4.

(Note: ellipses, and bracketed name, added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date MAY 31, 2014, and has the title “Business School, Disrupted.”)

Some of Christensen’s thoughts on higher education can be found in:

Christensen, Clayton M., and Henry J. Eyring. The Innovative University: Changing the DNA of Higher Education from the inside Out. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2011.

“On the topic of online instruction, Prof. Clayton Christensen said: ‘Do it cheap and simple. Get it out there.”” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.