“Cooking in Kohlua, India. Soot from tens of thousands of villages in developing countries is responsible for 18 percent of the planet’s warming, studies say.” Source of photo and caption: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Cooking in Kohlua, India. Soot from tens of thousands of villages in developing countries is responsible for 18 percent of the planet’s warming, studies say.” Source of photo and caption: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Economic growth is sometimes seen as increasing pollution. But the article quoted below shows that primitive cooking methods, which occur in the absence of economic growth, cause one of the most damaging forms of pollution: black carbon.

(p. A1) KOHLUA, India — “It’s hard to believe that this is what’s melting the glaciers,” said Dr. Veerabhadran Ramanathan, one of the world’s leading climate scientists, as he weaved through a warren of mud brick huts, each containing a mud cookstove pouring soot into the atmosphere.

As women in ragged saris of a thousand hues bake bread and stew lentils in the early evening over fires fueled by twigs and dung, children cough from the dense smoke that fills their homes. Black grime coats the undersides of thatched roofs. At dawn, a brown cloud stretches over the landscape like a diaphanous dirty blanket.

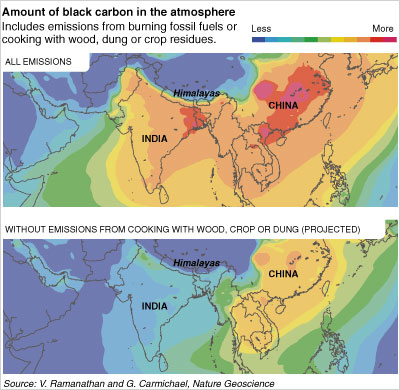

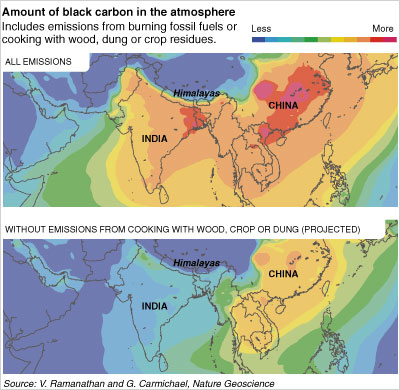

In Kohlua, in central India, with no cars and little electricity, emissions of carbon dioxide, the main heat-trapping gas linked to global warming, are near zero. But soot — also known as black carbon — from tens of thousands of villages like this one in developing countries is emerging as a major and previously unappreciated source of global climate change.

While carbon dioxide may be the No. 1 contributor to rising global temperatures, scientists say, black carbon has emerged as an important No. 2, with recent studies estimating that it is responsible for 18 percent of the (p. A12) planet’s warming, compared with 40 percent for carbon dioxide. Decreasing black carbon emissions would be a relatively cheap way to significantly rein in global warming — especially in the short term, climate experts say. Replacing primitive cooking stoves with modern versions that emit far less soot could provide a much-needed stopgap, while nations struggle with the more difficult task of enacting programs and developing technologies to curb carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels.

. . .

Better still, decreasing soot could have a rapid effect. Unlike carbon dioxide, which lingers in the atmosphere for years, soot stays there for a few weeks. Converting to low-soot cookstoves would remove the warming effects of black carbon quickly, while shutting a coal plant takes years to substantially reduce global CO2 concentrations.

. . .

Mark Z. Jacobson, professor of environmental engineering at Stanford, said that the fact that black carbon was not included in international climate efforts was “bizarre,” but “partly reflects how new the idea is.”

For the full story, see:

ELISABETH ROSENTHAL. “By Degrees; Black Carbon; Soot From Third-World Stoves Is New Target in Climate Fight.” The New York Times (Thurs., April 16, 2009): A1, A12.

(Note: ellipses added; the title of the online version is “By Degrees – Third-World Stove Soot Is Target in Climate Fight.” )

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.