(p. A2) For years, falling wages and high unemployment seemed proof that low-wage workers needed an entirely new set of skills to succeed in an economy shaped by technological change and globalization.

It turns out what they needed most was time. As the economic expansion reaches a record age and unemployment remains near generation lows, the fortunes of low-skilled workers have turned up markedly. What looked like a permanent setback may be mostly cyclical. Continue reading “Low-Skilled Workers Benefit from Economic Growth”

Category: Economic Growth

Boston Brahmins Invested in Western Industrialization

(p. A13) One of history’s ironies is that, even though New England birthed the abolition movement, many of Boston’s most prominent families offered less than total support for freeing the slaves. Their prosperity required a steady supply of cotton to feed New England’s growing textile industry. Even after slavery ended in 1865, wealthy Bostonians were reluctant to abandon their traditional business. Henry Lee Higginson, 30 years old and freshly discharged from the Union Army, bought with his partners a 5,000-acre plantation in Georgia with the goal of turning a profit by growing cotton. But the 60 former slaves living on the plantation thought the wages and terms offered to be grossly inadequate; the land they had worked in chains for generations, they believed, should belong to them. The enterprise soon collapsed.

As similar episodes played out across the South, Boston’s business elites looked for new places to invest their money. “They began to reenvision American capitalist development, not in modifying and salvaging the arrangements of earlier decades but in a far more ambitious program of continental industrialization,” Noam Maggor writes in “Brahmin Capitalism.” “They retreated from cotton and moved into a host of groundbreaking ventures in the Great American West—mining, stockyards, and railroads.”

. . .

Especially representative of the Bostonians’ transformative influence was Higginson’s next enterprise. Far removed from Georgian cotton, his interests landed on a copper mine in northern Michigan’s remote Keweenaw Peninsula. Copper had been discovered there 20 years earlier, but extraction had been small-scale and labor intensive; the high cost per unit meant that mining was profitable only for veins that contained at least 40% copper. In a short time, high-yield mines in the area began to show signs of depletion. But with Higginson’s capital—alongside investments from other Brahmins—large-scale copper extraction could take place as a continuous operation, making mining profitable on belts that contained only 2%-4% copper. In this way, Higginson’s Eastern capital transformed Western mining and launched a career that would make him one of Boston’s leading financiers.

For the full review, see:

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date June 25, 2017, and has the same title as the print version.)

The book under review is:

Maggor, Noam. Brahmin Capitalism: Frontiers of Wealth and Populism in America’s First Gilded Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Bill Gates Spending $400 Million to Develop Expensive High-Tech Toilets for Poor Countries

(p. B1) BEIJING — Bill Gates believes the world needs better toilets.

Specifically, toilets that improve hygiene, don’t have to connect to sewage systems at all and can break down human waste into fertilizer.

So on Tuesday in Beijing, Mr. Gates held the Reinvented Toilet Expo, a chance for companies to showcase their takes on the simple bathroom fixture. Companies showed toilets that could separate urine from other waste for more efficient treatment, that recycled water for hand washing and that sported solar roofs.

It’s no laughing matter. About 4.5 billion people — more than half the world’s population — live without access to safe sanitation. Globally, Mr. Gates told attendees, unsafe sanitation costs an estimated $223 billion a year in the form of higher health costs and lost productivity and wages.

The reinvented toilets on display are a culmination of seven years of research and $200 million given by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which the former software tycoon runs with his wife, since 2011. On Tuesday [Nov. 6, 2018], Mr. Gates pledged to give $200 million more in an effort get companies to see human waste as a big business.

. . .

(p. B5) . . . China’s toilet revolution has led to excesses — a problem that critics say could plague the Gates effort as well.

To win favor with Beijing, local officials have tried to outgun one another with newfangled latrines, many equipped with flat-screen televisions, Wi-Fi and facial-recognition toilet paper dispensers. (Thieves have been known to make off with entire rolls.) There were even refrigerators, microwave ovens and couches, prompting China’s tourism chief at the time to instruct officials in January to rein in their “five-star toilets” and avoid kitsch and luxury.

Though the products on display on Tuesday were nowhere as flashy, Mr. Gates has drawn criticism for giving thousands of dollars to universities in developed countries to create high-tech toilets that will take years to pay off — if they ever do.

“Sometimes doubling down is necessary, but you’ve got to be reflective,” said Jason Kass, the founder of Toilets for People, a Vermont-based social business that provides off-grid toilets. “Has any of the approaches done in the last five years created any sustainable lasting, positive impact vis-à-vis sanitation? And the answer, as far as I can see, is no.”

. . .

Mr. Gates acknowledged that some reinvented toilets, in small volumes, could cost as much as $10,000, but added, “That will pretty quickly come down.”

“The hard part will be getting it from $2,000 to $500,” he said. “I’d say we are more confident today that it was a good bet than where we started, but we are still not there.”

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses, and bracketed date, added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date Nov. 6, 2018, and has the title “In China, Bill Gates Encourages the World to Build a Better Toilet.”)

Economists Surprised by Inflation-Less Boom

(p. A13) The labor market the United States is experiencing right now wasn’t supposed to be possible.

Not that long ago, the overwhelming consensus among economists would have been that you couldn’t have a 3.6 percent unemployment rate without also seeing the rate of job creation slowing (where are new workers going to come from with so few out of work, after all?) and having an inflation surge (a worker shortage should mean employers bidding up wages, right?).

And yet that is what has happened, with the April employment numbers putting an exclamation point on the trend. The jobless rate receded to its lowest level in five decades. Employers also added 263,000 jobs; the job creation estimates of previous months were revised up; and average hourly earnings continued to rise at a steady rate — up 3.2 percent over the last year.

. . .

. . . beyond the assigning of credit or blame, there’s a bigger lesson in the job market’s remarkably strong performance: about the limits of knowledge when it comes to something as complex as the $20 trillion U.S. economy.

. . .

The results of the last few years make you wonder whether we’ve been too pessimistic about just how hot the United States economy can run without inflation or other negative effects.

There are even early signs that the tight labor market may be contributing to, or at least coinciding with, a surge in worker productivity, which if sustained would fuel higher wages and living standards over time. That further supports the case for the Fed and other policymakers to let the expansion rip rather than trying to hold it back.

For the full commentary, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the commentary has the date May 3, 2019, and has the title “The Economy That Wasn’t Supposed to Happen: Booming Jobs, Low Inflation.”)

“Longest Streak of Job Creation in Modern Times”

(p. A1) The unemployment rate fell to its lowest level in half a century last month, capping the longest streak of job creation in modern times and dispelling recession fears that haunted Wall Street at the start of the year.

The Labor Department reported Friday [May 3, 2019] that employers added 263,000 jobs in April, well above what analysts had forecast. The unemployment rate sank to 3.6 percent.

Employment has grown for more than 100 months in a row, and the economy has created more than 20 million jobs since the Great Recession ended in 2009. Much of that upturn occurred before President Trump was elected, but the obvious strength of the economy now enables him and fellow Republicans to make it their central argument in the 2020 campaign.

For the full story, see:

(Note: bracketed date added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date May 3, 2019, and has the title “Job Growth Underscores Economy’s Vigor; Unemployment at Half-Century Low.”)

Modi Cut India’s Taxes, Corruption, and Regulations

(p. B1) MUMBAI, India — A jeans maker saw his delivery costs cut by half when the highway police stopped asking for bribes. An aluminum wire factory faced only three inspectors rather than 12 to keep its licenses. Big companies like Corning, the American fiber-optic cable business, found they could wield a new bankruptcy law to demand that customers pay overdue bills.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi promised nearly five years ago to open India for business. Fitfully and sometimes painfully, his government has streamlined regulations, winnowed a famously antiquated bureaucracy and tackled corruption and tax evasion.

. . .

(p. B5) Mehta Creation, a jeans maker in a dilapidated concrete building in the northern outskirts, paid a welter of taxes until two years ago. That included the dreaded octroi, a British import from medieval times that allowed states and some cities to collect taxes whenever goods crossed a boundary.

Mehta Creation’s budget was contorted by corruption. To avoid the octroi, which could triple the cost of a delivery and add delays, Mehta paid drivers about $5 for each parcel of jeans and then reimbursed them up to $6 per parcel to bribe the local police at every border, said Dhiren Sharma, the company’s chief operating officer.

Mehta’s costs dropped after the government abolished 17 taxes, including the octroi, two years ago and established instead a national value-added tax on most business activity. Continue reading “Modi Cut India’s Taxes, Corruption, and Regulations”

Many Fewer Killed in Natural Disasters Than Were Killed 50 Years Ago

(p. A13) . . . it’s deceptive to track disasters primarily in terms of aggregate cost. Since 1990, the global population has increased by more than 2.2 billion, and the global economy has more than doubled in size. This means more lives and wealth are at risk with each successive disaster.

Despite this increased exposure, disasters are claiming fewer lives. Data tracked by Our World in Data shows that from 2007-17, an average of 70,000 people each year were killed by natural disasters. In the decade 50 years earlier, the annual figure was more than 370,000. Seventy thousand is still far too many, but the reduction represents enormous progress.

The material cost of disasters also has decreased when considered as a proportion of the global economy. Since 1990, economic losses from disasters have decreased by about 20% as a proportion of world-wide gross domestic product. The trend still holds when the measurement is narrowed to weather-related disasters, which decreased similarly as a share of global GDP even as the dollar cost of disasters increased.

For the full commentary, see:

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the commentary has the date Aug. 3, 2018, and has the same title as the print version.)

Pielke’s op-ed piece quoted above, is related to his book:

Pielke, Roger, Jr.. The Rightful Place of Science: Disasters & Climate Change. Tempe, AZ: Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes, 2018.

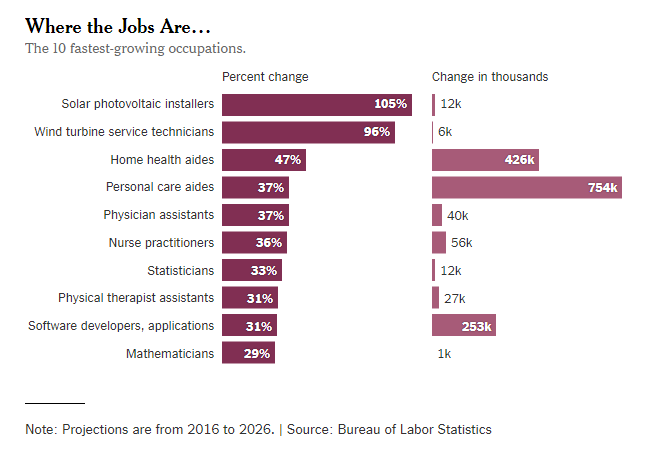

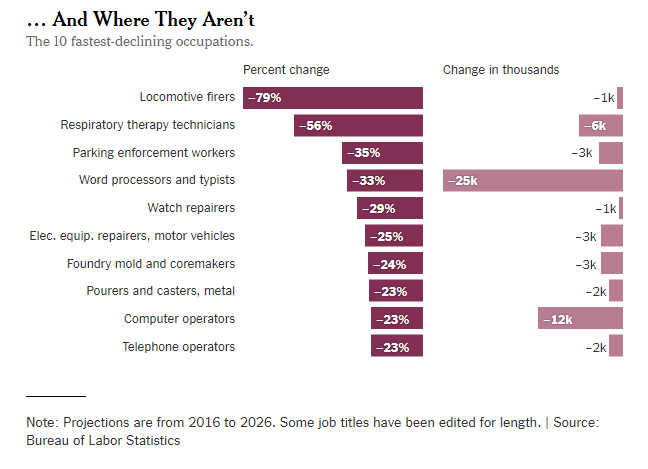

As Some Occupations Decline, Others Advance

(p. B3) . . . the impact of automation is increasingly spreading to the service sector as well. Government economists expect steep declines in employment for typists, telephone operators and data-entry workers. Even jobs that might once have seemed relatively secure, such as legal secretaries and executive assistants, are expected to decline in coming years.

At the same time, technology is creating new opportunities for statisticians, engineers and software developers — the workers developing the algorithms that are changing the global job market.

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date Oct. 24, 2017, and has the title “A Peek at Future Jobs Shows Growing Economic Divides.”)

Democrat Warren Buffett Admits to Being “a Card-Carrying Capitalist”

(p. B1) The most prominent face of capitalism — Warren Buffett, the avuncular founder of Berkshire and the fourth wealthiest person in the world, worth some $89 billion — appeared to distance himself from many of his peers, who have been apologizing for capitalism of late.

“I’m a card-carrying capitalist,” Mr. Buffett said. “I believe (p. B3) we wouldn’t be sitting here except for the market system,” he added, extolling the state of the economy. “I don’t think the country will go into socialism in 2020 or 2040 or 2060.”

There is something oddly refreshing about Mr. Buffett’s frankness.

. . .

Mr. Buffett’s moral code is one of being direct, even when it is not politically correct. In his plain-spoken way, Mr. Buffett, a longtime Democrat, acknowledged that the goal of capitalism was “to be more productive all the time, which means turning out the same number of goods with fewer people or churning out more goods, with the same number,” he said.

“That is capitalism.” Two years ago at the same meeting, he bluntly said, “I’m afraid a capitalist system will always hurt some people.”

. . .

. . . at his core, he believes that the pursuit of capitalism is fundamentally moral — that it creates and produces prosperity and progress even when there are immoral actors and even when it creates inequality.

. . .

One prominent chief executive I spoke with after the meeting said he wished he could speak as bluntly as Mr. Buffett. He said in this politically sensitive climate, he often has to tiptoe around controversial topics and at least nod at the societal concern of the moment.

Therein lies the truth of the particular moment that the business community faces and one that, at least so far, Mr. Buffett, at age 88, may be immune from.

And so while Mr. Buffett may have missed an opportunity to use his perch, he comes to his views of a just business world honestly.

For the full commentary, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the commentary has the date May 5, 2019, and has the title “Warren Buffett’s Case for Capitalism.”)

Are We “Made of Sugar Candy”?

(p. 11) Less a conventional history than an extended polemic, “Capitalism in America: A History,” by Greenspan and Adrian Wooldridge, a columnist and editor for The Economist, explores and ultimately celebrates the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter’s concept of “creative destruction,” which the authors describe as a “perennial gale” that “uproots businesses — and lives — but that, in the process, creates a more productive economy.”

. . .

. . . , Greenspan’s admiration for the rugged individualists who populate the novels of Ayn Rand (who merits a nod in this history) and the frontier spirit that animated America’s early development shows no sign of weakening as Greenspan has aged. He and Wooldridge lament that Americans are “losing the rugged pioneering spirit” that once defined them and mock the “trigger warnings” and “safe spaces” that now obsess academia.

The authors quote Winston Churchill: “We have not journeyed across the centuries, across the oceans, across the mountains, across the prairies, because we are made of sugar candy.” But now, they conclude, “sugar candy people are everywhere.”

Their prescription for American renewal — reining in entitlements, instituting fiscal responsibility and limited government, deregulating, focusing on education and opportunity, and above all fostering a fierceness in the face of creative destruction — was Republican orthodoxy not so long ago. Before the Great Recession it was embraced by most Democrats as well, and more recently by President Bill Clinton, the recipient of glowing praise in these pages.

No longer. “Capitalism in America,” in both its interpretation of economic history and its recipe for revival, is likely to offend the dominant Trump wing of the Republican Party and the resurgent left among Democrats. It’s not clear who, if anyone, will pick up the Greenspan torch.

For the full review, see:

James B. Stewart. “Creative Destruction.” The New York Times Book Review (Sunday, Nov. 4, 2018): 11.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date Nov. 2, 2018, and has the title “Alan Greenspan’s Ode to Creative Destruction.”)

The book under review, is:

Greenspan, Alan, and Adrian Wooldridge. Capitalism in America: A History. New York: Penguin Press, 2018.

Australia’s 27-Year Economic Expansion

(p. A2) Australia is experiencing an amazing economic run—a 27-year expansion that survived a regional economic crisis in the 1990s, a global economic crisis in the 2000s, and a boom-boost cycle in its core commodity sector in the 2010s.

Its experience offers lessons for the U.S. and the rest of the world. Among them, the laws of economics don’t dictate that expansions run on preset timetables. Wise policy-making, and some good luck, carried Australia’s expansion into the record books.

For the full commentary, see:

(Note: the online version of the commentary has the date July 15, 2018, and has the title “THE OUTLOOK; How an Economic Boom Can Run Out the Clock.”)