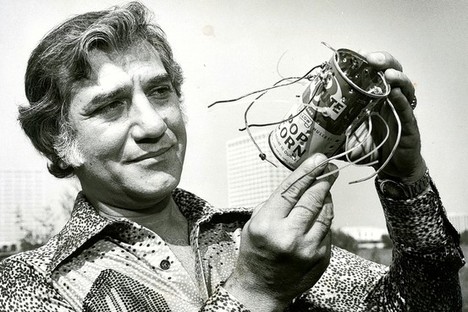

“Paul Holland and Molly Davis, producers of a new documentary, “Something Ventured,” that gives an admiring look at innovators and investors from the past.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Paul Holland and Molly Davis, producers of a new documentary, “Something Ventured,” that gives an admiring look at innovators and investors from the past.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. B3) The film, “Something Ventured,” is a frankly admiring look at those who went out on a limb to back upstarts like Atari, Cisco Systems, Genentech and Apple.

. . .

But the film’s beating heart is captured by Tom Perkins, whose Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers company backed the gene-splicing technology of Genentech, among other things. “It’s great if you can make money and change the world for the better at the same time,” said Mr. Perkins, . . .

Other stars of “Something Ventured” include Nolan Bushnell of Atari; Sandy Lerner of Cisco; Jimmy Treybig of Tandem Computers; and a string of venture capitalists, among them Don Valentine, Dick Kramlich, and Arthur Rock.

Many who appear joined dozens of other business people to finance the picture’s roughly $700,000 cost with contributions of a few thousand dollars each, Mr. Holland said.

In becoming involved, several participants said they wanted to rekindle an entrepreneurial spirit that had either waned or changed since the rough-and-tumble years when, by the film’s telling, Atari was started with $250 but needed capital to push Pong, and Mr. Bushnell passed up a chance to own a third of Apple, started by his employee Steve Jobs, for $50,000.

. . .

Mr. Valentine, . . . , said entrepreneurship had not ended — his company was a force behind Google — but it is less often coming from those born in the United States.

“You don’t understand what you have here” is a constant refrain, he said, from Southeast Asian and Indian innovators who are sometimes mystified by an American disdain for its own business culture.

For the full story, see:

MICHAEL CIEPLY . “A Film About Capitalism, and (Surprise) It’s a Love Story.” The New York Times, Week in Review Section (Sun., March 8, 2011): 8.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the story is dated March 7, 2011.)