Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

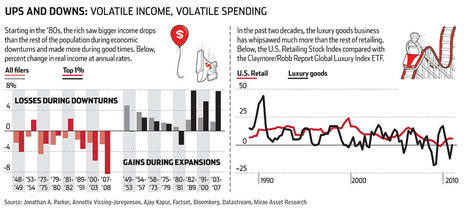

(p. C1) During the past three recessions, the top 1% of earners (those making $380,000 or more in 2008) experienced the largest income shocks in percentage terms of any income group in the U.S., according to research from economists Jonathan A. Parker and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen at Northwestern University. When the economy grows, their incomes grow up to three times faster than the rest of the country’s. When the economy (p. C2) falls, their incomes fall two or three times as much.

The super-high earners have the biggest crashes. The number of Americans making $1 million or more fell 40% between 2007 and 2009, to 236,883, while their combined incomes fell by nearly 50%–far greater than the less than 2% drop in total incomes of those making $50,000 or less, according to Internal Revenue Service figures.

. . .

“High beta” is a term used in financial markets to describe a stock or asset that has exaggerated up and down swings with the market. Tech start-ups and casino stocks have high betas, for example. Yet studies show that today’s rich have higher betas than many of the riskiest gambling stocks. Between 1947 and 1982, the beta of the top 1% was a modest 0.72, meaning that their incomes moved relatively in line with the rest of America. Between 1982 and 2007, their beta soared more than three-fold.

What created high-beta wealth? Economists aren’t sure. The rise of the high-betas and the rise in inequality started at the same time, suggesting they have a common cause. Mr. Parker and Ms. Vissing-Jorgenssen cite new communication technologies that allow the best workers and products to be scaled over larger markets, thus making them more sensitive to economic changes. Others cite globalization and the rise of “winner-take-all” pay schemes.

For the full commentary, see:

ROBERT FRANK. “The Wild Ride of the 1%; The once-stable incomes of America’s biggest earners now fluctuate dramatically from year to year. And as go the rich, so goes much of the economy.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., October 22, 2011): C1-C2.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

The Parker and Vissing-Jorgenssen paper is:

Parker, Jonathan A., and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen. “The Increase in Income Cyclicality of High-Income Households and Its Relation to the Rise in Top Income Shares.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, no. 2 (Fall 2010): 1-70.