Real-time electricity meters in a building in Central Park West behind resident Peter Funk, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Real-time electricity meters in a building in Central Park West behind resident Peter Funk, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

The article excerpted below gets some of the story right. It should emphasize more that the main benefit from real-time pricing would be that it would reduce the peak load. Generation plants need to be built to handle peak-load. The last generating plants to go on line are the least efficient. if the need for such inefficient, peak-load, plants can be reduced, the costs of generating electricity can be enormously reduced.

There is talk of market competition in the states that have deregulated their electric utility industries. But it should be remembered that even where most deregulated, the result is a long way from a paradigmatic free market. The main point is hinted at in the article below. The ultimate suppliers of electricity to the home remain government-protected monopolies.

If we wanted a truly free market, maybe we should actually allow multple companies to connect to homes, the way we allow multiple television and internet companies to connect their cables to the home. Then some low-cost Wal-Mart of electricty would arise, and blow the stick-in-the-muds away.

(p A1) Ten times last year, Judi Kinch, a geologist, got e-mail messages telling her that the next afternoon any electricity used at her Chicago apartment would be particularly expensive because hot, steamy weather was increasing demand for power.

Each time, she and her husband would turn down the air-conditioners — sometimes shutting one of them off — and let the dinner dishes sit in the washer until prices fell back late at night.

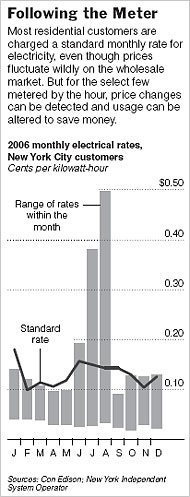

Most people are not aware that electricity prices fluctuate widely throughout the day, let alone exactly how much they pay at the moment they flip a switch. But Ms. Kinch and her husband are among the 1,100 Chicago residents who belong to the Community Energy Cooperative, a pilot project to encourage energy conservation, and this puts them among the rare few who are able to save money by shifting their use of power.

Just as cellphone customers delay personal calls until they become free at night and on weekends, and just as millions of people fly at less popular times because air fares are lower, people who know the price of electricity at any given moment can cut back when prices are high and use more when prices are low. Partici-(p. A14)pants in the Community Energy Cooperative program, for example, can check a Web site that tells them, hour by hour, how much their electricity costs; they get e-mail alerts when the price is set to rise above 20 cents a kilowatt-hour.

If just a fraction of all Americans had this information and could adjust their power use accordingly, the savings would be huge. Consumers would save nearly $23 billion a year if they shifted just 7 percent of their usage during peak periods to less costly times, research at Carnegie Mellon University indicates. That is the equivalent of the entire nation getting a free month of power every year.

. . .

Under either the traditional system of utility regulation, with prices set by government, or in the competitive business now in half the states, companies that generate and distribute power have little or no incentive to supply customers with hourly meters, which can cut into their profits.

Meters that encourage people to reduce demand at peak hours will translate to less need for power plants — particularly ones that are only called into service during streaks of hot or cold weather.

In states where rates are still regulated, utilities earn a virtually guaranteed profit on their generating stations. Even if a power plant runs only one hour a year, the utility earns a healthy return on its cost.

In a competitive market, it is the spikes in demand that cause prices to soar for brief periods. Flattening out the peaks would be disastrous for some power plant owners, which could go bankrupt if the profit they get from peak prices were to ebb significantly.

. . .

The smart metering programs are not new, but their continued rarity speaks in part to the success of power-generating companies in protecting their profit models. Some utilities did install meters in a small number of homes as early as three decades ago, pushed by the environmental movement and a spike in energy prices.

For the full story, see:

DAVID CAY JOHNSTON. "Taking Control Of Electric Bill, Hour by Hour." The New York Times (Mon., January 8, 2007): A1 & A14.

(Note: ellipses added.)

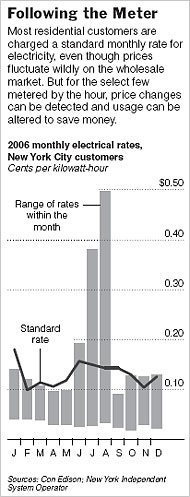

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.  Bernice Wilson’s kidney dialysis treatment includes the anti-anemia drug Epogen. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Bernice Wilson’s kidney dialysis treatment includes the anti-anemia drug Epogen. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above. CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below.

CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below.