The small dark blue squares indicate the “number of nations that have imposed protectionist measures on each country” and the light blue squares indicate the “number of measures imposed on each category of goods.” Source of quotations in caption and of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

The small dark blue squares indicate the “number of nations that have imposed protectionist measures on each country” and the light blue squares indicate the “number of measures imposed on each category of goods.” Source of quotations in caption and of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

(p. A5) BRUSSELS — This weekend’s U.S.-China trade skirmish is just the tip of a coming protectionist iceberg, according to a report released Monday by Global Trade Alert, a team of trade analysts backed by independent think tanks, the World Bank and the U.K. government.

A report by the World Trade Organization, backed by its 153 members and also released Monday, found “slippage” in promises to abstain from protectionism, but drew less dramatic conclusions.

Governments have planned 130 protectionist measures that have yet to be implemented, according to the GTA’s research. These include state aid funds, higher tariffs, immigration restrictions and export subsidies.

. . .

According to the GTA report, the number of discriminatory trade laws outnumbers liberalizing trade laws by six to one. Governments are applying protectionist measures at the rate of 60 per quarter. More than 90% of goods traded in the world have been affected by some sort of protectionist measure.

For the full story, see:

JOHN W. MILLER. “Protectionist Measures Expected to Rise, Report Warns.” The Wall Street Journal (Tues., SEPTEMBER 15, 2009): A5.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

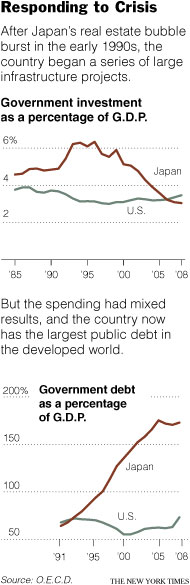

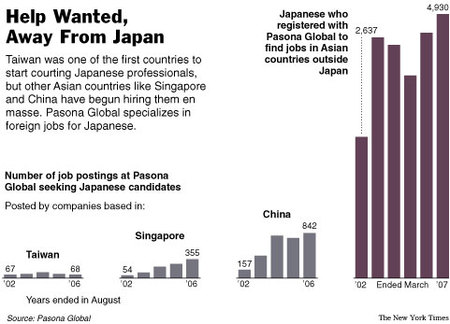

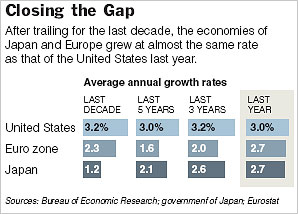

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.