Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Clayton Christensen, in a series of books, has highlighted why it is difficult for a successful incumbent to prepare a successor for its own winning product. The Motorola case below is another example.

Note, though, that Motorola’s failure is not the understandable one of failing to prepare what Christensen calls a "disruptive innovation." If the story below is right, it is a case of the less understandable failure to continue to deliver with what Christensen calls "sustaining innovation."

(p. A1) A year ago, Motorola Inc. appeared headed for a third straight year of rich profits under Chief Executive Ed Zander, driven by its hit cellphone the Razr. "A lot of you are always asking what is after the Razr," Mr. Zander said in an April 2006 conference call after another quarter of 30%-plus growth. "I say more Razrs."

But behind the scenes, Motorola was working furiously to get a successor phone to market by the second half of 2006, according to people familiar with the matter. When it failed to do so, profit margins on handsets narrowed and the company swung to a loss. Key executives left. And as the stock slid, activist investor Carl Icahn built up a position and began campaigning for a board seat to address what he called Motorola’s "operational problems."

Motorola’s travails illustrate the risks for a company that rides high with a big consumer hit. Amid its success with the Razr, it fell behind on developing a phone with the next generation of technology. Missing a beat is especially hazardous in cellphones, where it can take two to three years to develop a new line.

. . .

(p. A14) As the Razr grew hot, some former designers and engineers say Motorola repeated mistakes it had made a decade earlier with another big hit, the compact flip-top phone known as the StarTAC. That phone was a huge seller, but it also was an analog phone, and its popularity blinded the company to an industry shift to digital technology. Similarly, while Motorola was selling countless Razrs, competitors were hard at work on more sophisticated products for 3G networks.

Motorola put engineers and designers who could have been working on new products on the Razr and its derivatives, some former executives say. "All resources went to feeding the beast," says a former Motorola designer. "Suddenly, you created this thing that requires a lot of energy and attention." Other former executives dispute that the focus on the Razr diverted work from other products and contend Motorola was right to ride the still-popular Razr as long as possible.

For the full story, see:

CHRISTOPHER RHOADS and LI YUAN. "DROPPED CALL; How Motorola Fell A Giant Step Behind; As It Milked Thin Phone, Rivals Sneaked Ahead On the Next Generation." The Wall Street Journal (Fri., April 27, 2007): A1 & A14.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

The most complete source of Christensen’s theory and examples is:

Christensen, Clayton M., and Michael E. Raynor. The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2003.

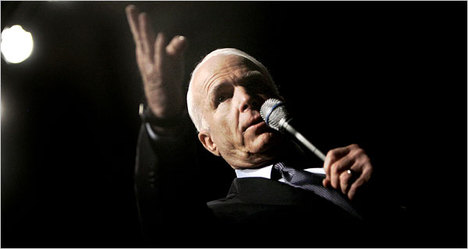

Motorola CEO. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Motorola CEO. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Motorola CEO. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Motorola CEO. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Source of the first and third graphic: the WSJ article cited above. Source of the second graphic: the NYT article cited above.

Source of the first and third graphic: the WSJ article cited above. Source of the second graphic: the NYT article cited above.