The fragility of success for large corporations is documented in the early chapters of the Foster and Kaplan book that is mentioned below.

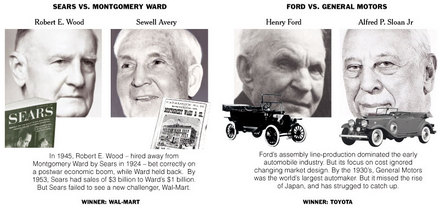

(p. 1) THE announcement last week that General Motors would cut 25,000 jobs and close several factories is yet another blow to the Goliath of automakers and its workers. But only if you work for G.M. is the company’s decline a worry. For consumers, the decline can be seen as a symbol of healthy competition.

G.M.’s sales, market share and work force have all been falling for a generation, even as the quality of its vehicles has gone up. Why? Because its competitors’ products have improved even more. Today’s auto buyers enjoy an unprecedented array of well-built, well-equipped, reasonably priced vehicles offered by many manufacturers.

. . .

(p. 3) . . . even if a new generation is drawn to G.M.’s products, recovery of its former position seems unlikely. Other brands have improved, too: J.D. Power estimates that for the auto industry overall, manufacturing defects declined 32 percent since 1998 alone.

There is also great pressure to hold prices down, which is bad for companies like G.M. with vast amounts of overhead. According to the consumer price index, new cars and light trucks today cost less in real-dollar terms than in 1982, despite having air bags, antilock brakes, CD players, power windows and other features either unavailable or considered luxury options back then.

This means that during the very period that General Motors has declined, American car buyers have become better off. Competition can have the effect of ”creative destruction,” in the economist Joseph Schumpeter’s famous term, harming workers in some places, while everyone else comes out ahead.

. . .

As it continues to shrink, G.M. may serve as an exemplar of what the world economy will do in many arenas — knock off established leaders, while improving quality and cutting prices. In their 2001 book ”Creative Destruction,” Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan, analysts at McKinsey & Company, documented how even powerhouse companies that are ”built to last” usually succumb to competition.

Competition can be a utilitarian force that brings the greatest good to the greatest number. Someday when the remaining divisions of General Motors are bought by some start-up company that doesn’t even exist yet, try to keep that in mind.

For the full commentary, see:

(Note: the ellipsis in the title is in the original title; the ellipses in the article, were added.)

The full reference to the Foster and Kaplan book, is:

Foster, Richard and Sarah Kaplan. Creative Destruction: Why Companies that Are Built to Last Underperform the Market—and How to Successfully Transform Them. New York: Currency Books, 2001.

Charles Koch. Source of image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Charles Koch. Source of image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Gary Becker at April 7, 2006 tribute dinner. Source of image: online press release cited below.

Gary Becker at April 7, 2006 tribute dinner. Source of image: online press release cited below.