(p. A1) WASHINGTON — A wave of optimism has swept over American business leaders, and it is beginning to translate into the sort of investment in new plants, equipment and factory upgrades that bolsters economic growth, spurs job creation — and may finally raise wages significantly.

While business leaders are eager for the tax cuts that take effect this year, the newfound confidence was initially inspired by the Trump administration’s regulatory pullback, not so much because deregulation is saving companies money but because the administration has instilled a faith in business executives that new regulations are not coming.

“It’s an overall sense that you’re not going to face any new regulatory fights,” said Granger MacDonald, a home builder in Kerrville, Tex. “We’re not spending more, which is the main thing. We’re not seeing any savings, but we’re not seeing any increases.”

. . .

(p. A10) Only a handful of the federal government’s reams of rules have actually been killed or slated for elimination since Mr. Trump took office. But the president has declared that rolling back regulations will be a defining theme of his presidency. On his 11th day in office, Mr. Trump signed an executive order “on reducing regulation and controlling regulatory costs,” including the stipulation that any new regulation must be offset by two regulations rolled back.

That intention and its rhetorical and regulatory follow-ons have executives at large and small companies celebrating. And with tax cuts coming and a generally improving economic outlook, both domestically and internationally, economists are revising growth forecasts upward for last year and this year.

. . .

. . . economists see a plausible connection between Mr. Trump’s determination to prune the federal rule book and the willingness of businesses to crank open their vaults. Measures of business confidence have climbed to record heights during Mr. Trump’s first year.

. . .

“We have spent the past dozen years or longer operating in environments that have had an increasing regulatory burden,” said Michael S. Burke, the chairman and chief executive of Aecom, a Los Angeles-based multinational consulting firm that specializes in infrastructure projects. “That burden has slowed down economic growth, it’s slowed down investment in infrastructure. And what we’ve seen over the last year is a big deregulatory environment.”

. . .

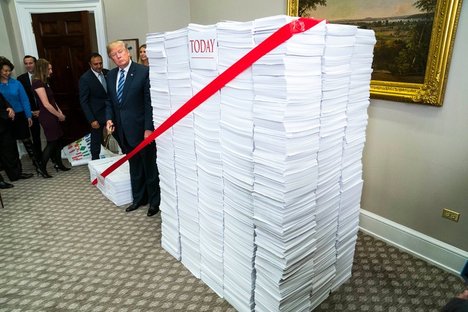

The White House sees its efforts as having their intended effect. Mr. Trump boasted about his deregulatory efforts last month at an event where he stood in front of a small mountain of printouts representing the nation’s regulatory burden and ceremonially cut a large piece of “red tape.”

The chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, Kevin Hassett, said in an interview that the administration’s freeze on new regulations, in particular, appeared to have buoyed confidence. Though he cautioned that it could take years of research to pin down the magnitude of the effects, he said deregulation was “the most plausible story” to explain why economic growth in 2017 had outstripped most forecasts.

“Our view is, the ‘no new regulations’ piece has to be more powerful than we thought,” he said.

For the full story, see:

BINYAMIN APPELBAUM and JIM TANKERSLEY. “With Red Tape Losing Its Grip, Firms Ante Up.” The New York Times (Tues., January 2, 2018): A1 & A10.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date JAN. 1, 2018, and has the title “The Trump Effect: Business, Anticipating Less Regulation, Loosens Purse Strings.”)