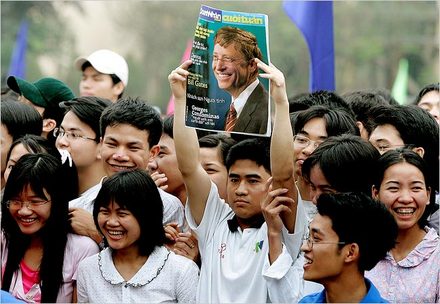

Vietnamese university students hoping to see Bill Gates. Source of image: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/27/world/asia/27vietnam.html?ex=1303790400&en=255d4d4996b1a9a6&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss

Vietnamese university students hoping to see Bill Gates. Source of image: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/27/world/asia/27vietnam.html?ex=1303790400&en=255d4d4996b1a9a6&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss

HANOI, Vietnam, April 26 — It was Lenin’s birthday. The most important Communist Party meeting in five years was under way. And the star of the show was the world’s most famous capitalist, Bill Gates.

The president, the prime minister and the deputy prime minister all excused themselves from the party meeting on Saturday to have their pictures taken with Mr. Gates, who has more star power in Vietnam than any of them.

When people heard he was in town, hundreds climbed trees and pushed through police lines to get a glimpse of him. He was the subject of the lead article in the next day’s newspapers.

This is where Vietnam stands today, moving cautiously toward a new version of communism while the people and their leaders lunge eagerly for the brass ring of capitalist development.

"That was very symbolic," said Le Dang Doanh, an official in the Ministry of Planning, speaking of the reception for Mr. Gates. "It is a very clear sign of the new mood of society and the people. Everybody wants to be like Bill Gates."

For the full story, see:

Note: the version of the article above corrects an error in the print version that had misidentified the day of Lenin’s birth, and Gates visit as a Sunday (it was a Saturday).

Charles Koch. Source of image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Charles Koch. Source of image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

David Leonhardt. Source of image:

David Leonhardt. Source of image: