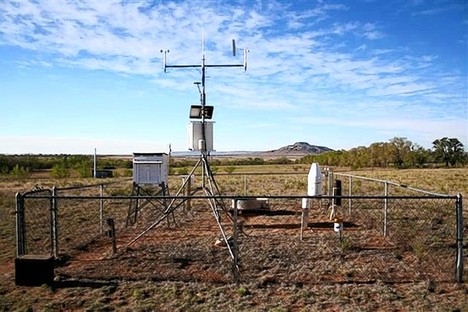

“Well-sited weather stations, like the one at top in Tucumcari, N.M., are more reliable than others, such as one in a Tuscon, Ariz., parking lot.” Source of caption: print version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

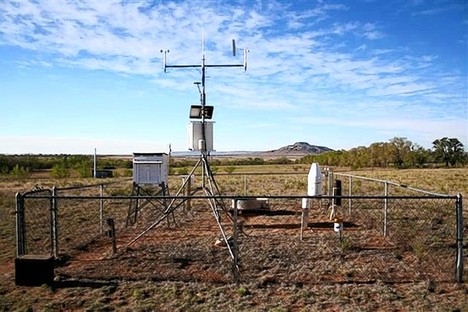

“Well-sited weather stations, like the one at top in Tucumcari, N.M., are more reliable than others, such as one in a Tuscon, Ariz., parking lot.” Source of caption: print version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below. Source of photos: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

(p. A2) “Before us, there was a huge barrier to entry” in the field of analyzing temperature numbers, says Richard Muller, scientific director of the Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature team and a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Many scientists are giving the Berkeley Earth team kudos for creating the unified database.

. . .

“I’m inclined to give [satellite] data more weight than reconstructions from surface-station data,” says Stephen McIntyre, a Canadian mathematician who writes about climate, often critically of studies that find warming, at his website Climate Audit. Satellites show about half the amount of warming as that of land-based readings in the past three decades, when the relevant data were collected from space, he says.

Such disputes demonstrate the statistical and uncertain nature of tracking global temperature. Even with tens of thousands of weather stations, most of the Earth’s surface isn’t monitored. Some stations are more reliable than others. Calculating a global average temperature requires extrapolating from these readings to the whole globe, adjusting for data lapses and suspect stations. And no two groups do this identically.

. . .

Calculating a global temperature is necessary to track climate trends because, as your TV meteorologist might warn, local conditions can differ. Much of the U.S. and Northern Europe has cooled in the last 70 years, Berkeley Earth found. So did one-third of all weather stations world-wide, while two-thirds warmed. The project cites this as evidence of overall warming; skeptics aren’t convinced because it depends how concentrated those warming sites are. If they happen to be bunched up while the cooling sites are in sparsely measured areas, then more places could be cooling.

. . .

Any statistical model produces results with some level of uncertainty. The Berkeley Earth project is no different. That uncertainty is large enough to dwarf some trends in temperature. For instance, fluctuations in the land temperature for the past 13 years make it extremely difficult to say whether the Earth has been continuing to warm during that time.

This possible halting of the temperature rise led to a dispute between members of the Berkeley Earth team. Judith Curry, Mr. Muller’s co-author and a professor of earth and atmospheric sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, told a reporter for the Daily Mail she questioned Mr. Muller’s claim, which he published in an opinion column in The Wall Street Journal, that “you should not be a skeptic, at least not any longer.” She said that if the global temperature has flattened out, that would raise new questions, and scientific skepticism would remain warranted.

For the full story, see:

CARL BIALIK. “THE NUMBERS GUY; Global Temperatures: All Over the Map.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., November 5, 2011): A2.

(Note: ellipses added.)