Source of book image: http://www.awn.com/files/imagepicker/23/artofpeanuts-cover-620.jpg

(p. C10) Of all the “Peanuts” television specials ever made, the first–“A Charlie Brown Christmas” (1965)–was the Charlie Browniest. The 25-minute special was an underdog, just like its hapless protagonist, and barely made it on the air. CBS gave producer Lee Mendelson so minuscule a budget, we learn in Charles Solomon’s “The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation,” that he was forced to fund the rest out of his own pocket–even though Coca-Cola had already guaranteed sponsorship. When “A Charlie Brown Christmas” pulled in sensational ratings, CBS grudgingly asked for follow-ups. “We’re going to order four more,” a network executive told Mr. Mendelson, “though my aunt in New Jersey didn’t like it either”–a line that Schulz might have written.

. . .

“A Charlie Brown Christmas” established the template, mixing morals and gags in a way that made the peachiness seem endearing. The perfectly pitched dialogue, written by Schulz himself, was voiced (at his insistence) by actual children. The expressionist use of line and color was introduced by director Bill Melendez, and the understated yet supremely catchy Latin jazz scores were the work of pianist-composer Vince Guaraldi and his combo. The tune Guaraldi called “Linus and Lucy” came to be synonymous with “Peanuts” for the generations that grew up on the specials.

While the movements of the characters–especially Snoopy–could be antic, Guaraldi’s scores set a cool counterpoint and provided a sense of serenity that was utterly unique. The characters weren’t always moving–sometimes they would stop and simply listen to each other–and Schulz insisted that there be no laugh track. He made the climax of the drama Linus walking to the center of the school stage to recite from the gospel of Luke–a decision daring even in its day, not least because it stopped the action for an extended period to show a hand-drawn character delivering a lisping speech.

For the full review, see:

WILL FRIEDWALD. “BOOKSHELF; Cheers for Chuck.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., December 22, 2012): C10.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date December 21, 2012.)

Book under review:

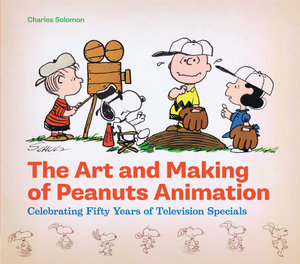

Solomon, Charles. The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation: Celebrating Fifty Years of Television Specials. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books, 2012.