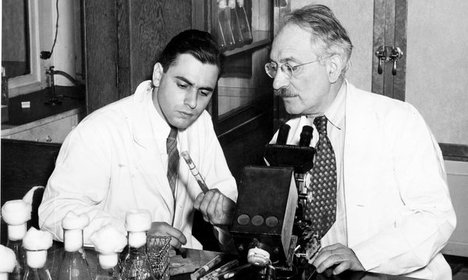

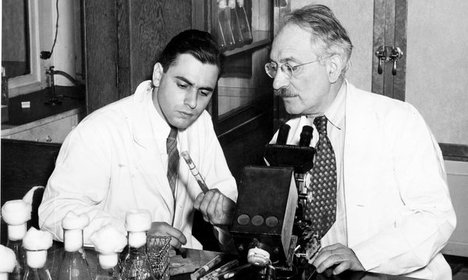

“EVIDENCE; A lab notebook belonging to Albert Schatz, left, with his supervisor, Selman A. Waksman, and discovered at Rutgers helps puts to rest a 70-year argument over credit for the Nobel-winning discovery of streptomycin.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“EVIDENCE; A lab notebook belonging to Albert Schatz, left, with his supervisor, Selman A. Waksman, and discovered at Rutgers helps puts to rest a 70-year argument over credit for the Nobel-winning discovery of streptomycin.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. D3) NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J. — For as long as archivists at Rutgers University could remember, a small cardboard box marked with the letter W in black ink had sat unopened in a dusty corner of the special collections of the Alexander Library. Next to it were 60 sturdy archive boxes of papers, a legacy of the university’s most famous scientist: Selman A. Waksman, who won a Nobel Prize in 1952 for the discovery of streptomycin, the first antibiotic to cure tuberculosis.

The 60 boxes contained details of how streptomycin was found — and also of the murky story behind it, a vicious legal battle between Dr. Waksman and his graduate student Albert Schatz over who deserved credit.

Dr. Waksman died in 1973; after Dr. Schatz’s death in 2005, the papers were much in demand by researchers trying to piece together what really happened between the professor and his student. But nobody looked in the small cardboard box.

. . .

Thomas J. Frusciano, the head archivist of the Alexander Library special collections, recalled that the Waksman papers had been acquired in 1983, 10 years after the professor’s death, and had even included a vial of streptomycin. He asked a member of his team, Erika Gorder, to search the stacks.

She remembered seeing the small box next to Dr. Waksman’s papers. “I must have passed by it a million times,” she said, “but I always thought it must contain miscellaneous material from the Waksman papers when they were cataloged.”

When she pulled down the box and carefully opened it, however, there, loosely piled inside, were five clothbound notebooks — just like Dr. Waksman’s, but marked “Albert Schatz.”

In the notebook for 1943, on Page 32, Dr. Schatz had started Experiment 11. In meticulous cursive, he had written the date, Aug. 23, and the title, “Exp. 11 Antagonistic Actinomycetes,” a reference to the strange threadlike microbes found in the soil that produce antibiotics. Underneath the title he recorded where he had found the microbes in “leaf compost, straw compost and stable manure” on the Rutgers College farm, outside his laboratory.

The following pages detailed his experiments and his discovery of two strains of a gray-green actinomycete named Streptomyces griseus, Latin for gray. Each strain produced an antibiotic that destroyed germs of E. coli in a petri dish — and, he was to find out later, also destroyed the TB germ. The notebook shows that the moment of discovery belongs to Dr. Schatz.

One of the pages in Experiment 11 had indeed been cut out, but the page was toward the end of the experiment, after Dr. Schatz had made his discovery. There was no evidence of a break in the experiment to suggest that Dr. Schatz might have removed the page to conceal something he didn’t want the rest of the world to know.

And in Dr. Waksman’s own papers — in the 60 boxes — there was confirmation that the professor knew the missing page was not a real issue. His legal advisers had told him bluntly that it was a distraction. As one lawyer wrote, the missing page was “insignificant.”

As for the professor’s story that Dr. Schatz’s uncle had carried off the key 1943 notebook, Dr. Waksman’s own documents make clear it could not have been true. At the time the key notebook was not at Rutgers; it was with university-appointed agents who were preparing the streptomycin patent application. Here, indeed, was evidence that Dr. Waksman had deliberately spread doubt and confusion about Dr. Schatz’s Experiment 11 in a campaign to belittle the work of his student.

For the full story, see:

PETER PRINGLE. “Notebooks Shed Light on an Antibiotic’s Contested Discovery.” The New York Times (Tues., June 12, 2012): D3.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date June 11, 2012.)

The issues treated above are discussed in more detail in Pringle’s book:

Pringle, Peter. Experiment Eleven: Dark Secrets Behind the Discovery of a Wonder Drug. New York: Walker & Company, 2012.