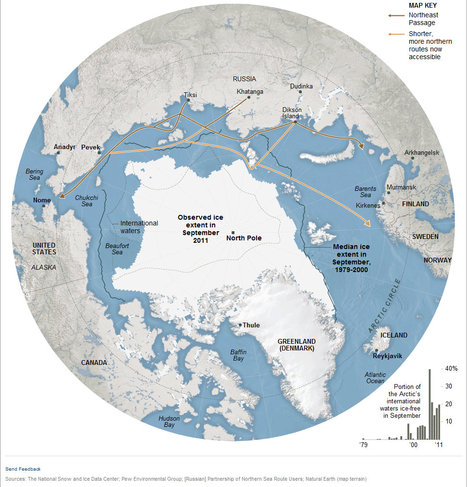

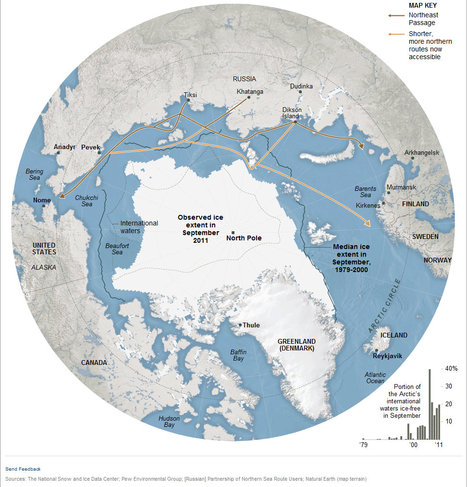

“The Northeast Passage Opens Up. The Arctic ice cap has been shrinking, opening up new shipping lanes. This has given access to oil and gas fields, as well as fishing in international waters that were not accessible before.” Source of caption and map: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“The Northeast Passage Opens Up. The Arctic ice cap has been shrinking, opening up new shipping lanes. This has given access to oil and gas fields, as well as fishing in international waters that were not accessible before.” Source of caption and map: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. B1) ARKHANGELSK, Russia — Rounding the northernmost tip of Russia in his oceangoing tugboat this summer, Capt. Vladimir V. Bozanov saw plenty of walruses, some pods of beluga whales and in the distance a few icebergs.

One thing Captain Bozanov did not encounter while towing an industrial barge 2,300 miles across the Arctic Ocean was solid ice blocking his path anywhere along the route. Ten years ago, he said, an ice-free passage, even at the peak of summer, was exceptionally rare.

But environmental scientists say there is now no doubt that global warming is shrinking the Arctic ice pack, opening new sea lanes and making the few previously navigable routes near shore accessible more months of the year. And whatever the grim environmental repercussions of greenhouse gas, companies in Russia and other countries around the Arctic Ocean are mining that dark cloud’s silver lining by finding new opportunities for commerce and trade.

Oil companies might be the most likely beneficiaries, as the receding polar ice cap opens more of the sea floor to exploration. The oil giant Exxon Mobil recently signed a sweeping deal to drill in the Russian sector of the Arctic Ocean. But shipping, mining and fishing ventures are also looking farther north than ever before.

“It is paradoxical that new opportunities are opening for our nations at the same time we understand that the threat of (p. B13) carbon emissions have become imminent,” Iceland’s president, Olafur Ragnar Grimsson, said at a recent conference on Arctic Ocean shipping held in this Russian port city not far south of the Arctic Circle.

At the same forum, Prime Minister Vladimir V. Putin of Russia offered a full-throated endorsement of the new business prospects in the thawing north.

“The Arctic is the shortcut between the largest markets of Europe and the Asia-Pacific region,” he said. “It is an excellent opportunity to optimize costs.”

For the full story, see:

ANDREW E. KRAMER. “Amid the Peril, a Dream Fulfilled.” The New York Times (Tues., October 18, 2011): B1 & B13.

(Note: the online version of the article is dated October 17, 2011 and has the title “Warming Revives Dream of Sea Route in Russian Arctic.”)

“The tanker Vladimir Tikhonov in the Bering Strait.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“The tanker Vladimir Tikhonov in the Bering Strait.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak uses the voice feature on his new Apple iPhone 4S at the Apple Store in Los Gatos, Calif., on Friday. Wozniak, who created Apple with Steve Jobs in a Silicon Valley garage in 1976, waited 20 hours in line to be the first customer at the store to buy the new iPhone.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the Omaha World-Herald article cited below.

“Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak uses the voice feature on his new Apple iPhone 4S at the Apple Store in Los Gatos, Calif., on Friday. Wozniak, who created Apple with Steve Jobs in a Silicon Valley garage in 1976, waited 20 hours in line to be the first customer at the store to buy the new iPhone.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the Omaha World-Herald article cited below.