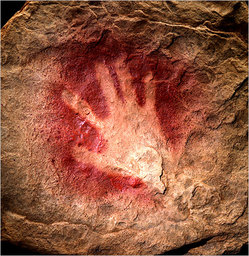

“The David H. Koch Hall of Human Origins in Washington includes this 30,000-year-old handprint from France.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. C32) The exhibition’s theme is “What Does It Mean to Be Human?” And the new image of the human it creates is different from the one from a century ago. It isn’t that nature has suddenly become a pastoral paradise. Some of the most unusual objects here are fossilized human bones bearing scars of animal attacks: a 3-year-old’s skull from about 2.3 million years ago is marked by eagle talons in the eye sockets; an early human’s foot shows the bite marks of a crocodile. In one of the exhibition’s interactive video stations, in which you are cleverly shown how excavated remains are interpreted, you learn that the teeth of a leopard’s lower jaw found in a cave at the Swartkrans site in South Africa match the puncture marks in a nearby early-human skull: evidence of a 1.8 million-year-old killing.

. . .

During the brief 200,000-year life of Homo sapiens, at least three other human species also existed. And while this might seem to diminish any remnants of pride left to the human animal in the wake of Darwin’s theory, the exhibition actually does the opposite. It puts the human at the center, tracing how through these varied species, central characteristics developed, and we became the sole survivors. The show humanizes evolution. It is, in part, a story of human triumph.

. . .

. . . at recent excavations in China, at Majuangou, stone tools were found in four layers of rock dating from 1.66 million to 1.32 million years ago; fossil pollen proved that each of these four time periods was also associated with a different habitat. “The toolmaker, Homo erectus,” we read, “was able to survive in all of these habitats.”

That ability was crucial. The hall emphasizes that enormous changes in the planet’s climate accompanied hominin development, suggesting that the ability to adapt to such differing circumstances was the human’s strength. Climate change was one of the forces that led to the triumph of Homo sapiens.

For the full review, see:

EDWARD ROTHSTEIN. “Exhibition Review; Hall of Human Origins; Searching the Bones of Our Shared Past.” The New York Times (Fri., March 19, 2010): C25 & C32.

(Note: italics in original; ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the review is dated March 18, 2010.)