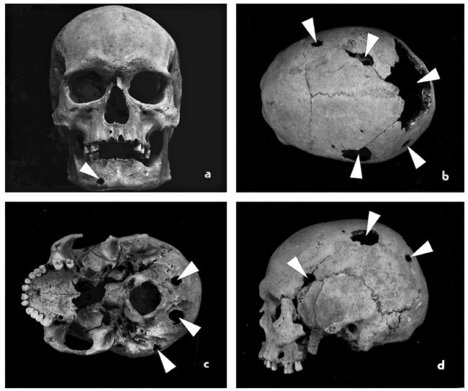

“DIAGNOSIS. Evidence of tumors in the skull of a male skeleton exhumed from an early medieval cemetery in Slovakia. Often thought of as a modern disease, cancer has always been with us.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“DIAGNOSIS. Evidence of tumors in the skull of a male skeleton exhumed from an early medieval cemetery in Slovakia. Often thought of as a modern disease, cancer has always been with us.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. D1) When they excavated a Scythian burial mound in the Russian region of Tuva about 10 years ago, archaeologists literally struck gold. Crouched on the floor of a dark inner chamber were two skeletons, a man and a woman, surrounded by royal garb from 27 centuries ago: headdresses and capes adorned with gold horses, panthers and other sacred beasts.

But for paleopathologists — scholars of ancient disease — the richest treasure was the abundance of tumors that had riddled almost every bone of the man’s body. The diagnosis: the oldest known case of metastasizing prostate cancer.

The prostate itself had disintegrated long ago. But malignant cells from the gland had migrated according to a familiar pattern and left identifiable scars. Proteins extracted from the bone tested positive for PSA, prostate specific antigen.

Often thought of as a modern disease, cancer has always been with us.

. . .

(p. D7) . . . , Tony Waldron, a paleopathologist at University College London, analyzed British mortality reports from 1901 to 1905 — a period late enough to ensure reasonably good records and early enough to avoid skewing the data with, for example, the spike in lung cancer caused in later decades by the popularity of cigarettes.

Taking into account variations in life span and the likelihood that different malignancies will spread to bone, he estimated that in an “archaeological assemblage” one might expect cancer in less than 2 percent of male skeletons and 4 to 7 percent of female skeletons.

Andreas G. Nerlich and colleagues in Munich tried out the prediction on 905 skeletons from two ancient Egyptian necropolises. With the help of X-rays and CT scans they diagnosed five cancers — right in line with Dr. Waldron’s expectations. And as his statistics predicted, 13 cancers were found among 2,547 remains buried in an ossuary in southern Germany between A.D. 1400 and 1800.

For both groups, the authors wrote, malignant tumors “were not significantly fewer than expected” when compared with early-20th-century England. They concluded that “the current rise in tumor frequencies in present populations is much more related to the higher life expectancy than primary environmental or genetic factors.”

. . .

“Cancer is an inevitability the moment you create complex multicellular organisms and give the individual cells the license to proliferate,” said Dr. Weinberg of the Whitehead Institute. “It is simply a consequence of increasing entropy, increasing disorder.”

He was not being fatalistic. Over the ages bodies have evolved formidable barriers to keep rebellious cells in line. Quitting smoking, losing weight, eating healthier diets and taking other preventive measures can stave off cancer for decades. Until we die of something else.

“If we lived long enough,” Dr. Weinberg observed, “sooner or later we all would get cancer.”

For the full story, see:

GEORGE JOHNSON. “Unearthing Prehistoric Tumors, and Debate.” The New York Times (Tues., December 28, 2010): D1 & D7.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated December 27, 2010.)