My Wabash economics prof Ben Rogge used to say that rulers have always liked to spend the people’s money to build pyramids intended to proclaim the glory of the ruler. But in modern times the rulers have to be a tad more subtle than the Egyptians, so, for instance, in Brazil they build Brazilia, instead of actual pyramids.

And according to the story below, summarized from the May 2007 IEEE Spectrum, in Africa, they build large dams.

Small dams could help deliver electricity to much of Africa’s population, but since they lack the prestige of larger-scale projects, few of them get built.

. . .

In Uganda, which has plenty of rivers and streams to supply power, Mr. Zachary describes how a small water-power generator, supplied by a small nearby dam, delivers 60 kilowatts of energy to a nearby hospital. The generator would barely be enough to run a single magnetic-resonance imaging machine, a staple in Western hospitals. But it does provide enough power to light the hospital and keep basic equipment running for the 100 nurses and doctors who work there. The entire generation system cost $15,000 to build.

Still, Africa’s leaders are unlikely to abandon their preference for big public works, says Mr. Zachary, since they create thousands of construction jobs and reinforce the political might of the central government.

For the full summary, see:

(Note: ellipsis added; the original article in IEEE Spectrum is by G. Pascal Zachary.)

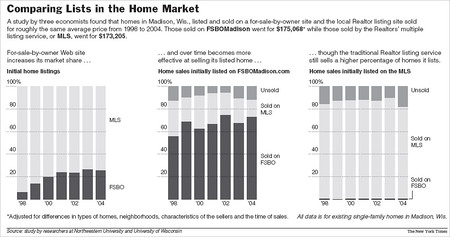

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.