Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

In the Thursday, November 10, 2011 “Home” section of The New York Times, the lead article was about a surge in demand for personal electricity generators among the middle-class of the northeastern United States (places like Connecticut).

Perhaps the lesson is that “green” is a passing fad, but electric power is a necessity in preserving bedrock values such as light, warmth and communication?

(p. D1) WHEN the snowstorm hit a week ago Saturday, Evan Sidel was driving home from the supermarket, having stocked up on soup ingredients, thinking she and her two daughters would have a cozy evening in. But while she was unpacking the groceries, the power went out with an audible bang, said Ms. Sidel, who lives in a 100-year-old farmhouse in Wilton, Conn.

“You could literally hear the transformer exploding,” she said.

Then things went south fast, escalating perilously like the plot of an action movie, or “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark” in previews. As Ms. Sidel pulled an old land-line telephone out of the closet, one birch tree crashed into the side of her house and another into her front door.

“I called a friend who said, ‘My generator has just kicked in, come on over.’ I got out through the garage, drove over the lawn to the street, and I stayed at my friend’s house until Wednesday,” she recounted.

. . .

(p. D7) The back story to the recent biblical weather was the Great Generator Divide. With hundreds of thousands of households without power last week — nearly 800,000 in Connecticut alone — who had a generator (and how big it was) was the second most urgent topic in New Jersey, New York and Connecticut. Generator envy ran wide and deep as the staccato growl and smoky breath of portable generators defined the haves and the have-nots in many neighborhoods.

. . .

A few months ago, Mr. Petersheim offered to retrofit the houses he had built in Barryville, N.Y., with standby generators.

“We were seeing more and more power outages in that area,” he said. “And it’s not a super-high-priority area, so the power can stay out for days. Pipes can freeze, food spoils, you can’t get water. It’s become a stress point for our customers. I sent out an e-mail to 20 of them saying, ‘If you’re getting too annoyed with this, it’s pretty affordable, under $7,000 for a 14-kilowatt Generac fueled by propane.’ Seven took us up on it.”

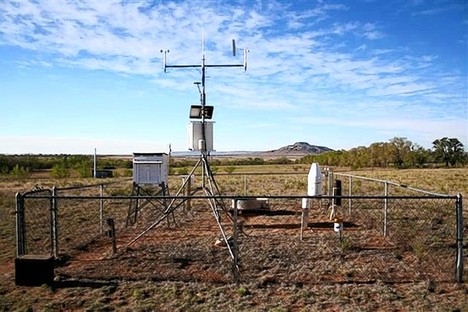

Courtney and Bronson Bigelow (she’s in public relations, he’s a lawyer) were among them. “The first time we had a power outage, it was kind of romantic,” Ms. Bigelow said. “But then it kept happening. When you’re trying to squeeze every second of your weekend, it’s a huge bummer. You can’t wash dishes, you can’t wash yourself, and it’s 20 degrees. This summer we had this freakish weather, torrential rains over Fourth of July, then these weird microburst thunderstorms, and then Irene.”

. . .

Over in Lakeville, Conn., Allen Cockerline, who raises grass-fed cattle with his wife, Robin, at their Whippoorwill Farm, has two large portable generators, 10 and 15 kilowatts each. One runs off his tractor; the other is powered by gasoline. (The tractor-powered one he bought with the farm; the other one cost about $1,500, he said.)

They are a necessary insurance policy for a perishable product, he said: “There’s $30,000 worth of beef in my freezer. I’m not going to let that go.”

But armed as he is against calamity, Mr. Cockerline will admit to some generator envy.

“Everyone that surrounds me is on a much more turnkey situation,” he said. “Theirs just go on automatically. They don’t have to go out and move tractors and generators around.”

“My system is down-and-dirty,” he added, and “in that respect I have a certain amount of envy. But I’m sure my generators are bigger than theirs. Much bigger.”

For the full story, see:

PENELOPE GREEN. “Dark with Envy.” The New York Times (Thurs., November 10, 2011): D1 & D7.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated November 9, 2011 and had the title “Power Envy.”)

“Courtney and Bronson Bigelow and their Generac generator in Sullivan County, N.Y.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Allen and Robin Cockerline with one of their two portable generators, in Lakeville, Conn.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.