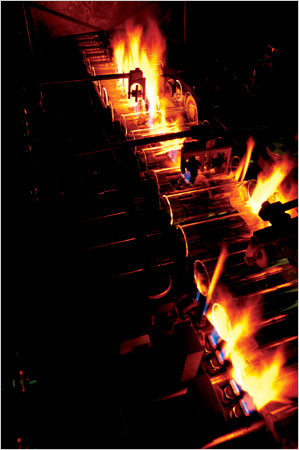

“Making glass has long been energy-intensive, but soaring energy prices provide a strong incentive for that to change.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. 4) Glassmaking is a based on old, stable technologies that require lots of materials and energy. The basic furnace, which melts sand into glass at extremely high temperatures, hasn’t undergone a fundamental change since the 1850s. Furnace designers have long contented themselves with small improvements, such as using pure oxygen to improve energy efficiency.

Today, glassmaking faces a technological upheaval that offers a reminder that “it is a mistake to assume that older technologies are less dynamic than new ones,” says David Edgerton, a historian at Imperial College in London and the author of “The Shock of the Old,” a history of the evolution of pre-electronic technologies in the 20th century.

. . .

Mr. Greenman sees a new willingness to innovate among glassmakers who, until recently, usually shunned technological advances because savings in materials and energy didn’t justify the costs of introducing new designs and processes.

“Many innovations were, frankly, thwarted by cost,” says C. Philip Ross, a consultant in Laguna Niguel, Calif., who has studied technological options for the industry. “There’s a lot of upside in revisiting old, discarded ideas.”

Glassmakers are searching for both small and large advances on three fronts: designing more efficient furnaces; creating much stronger glass; and using heat better.

. . .

The potential revolution in glass-making suggests a new model for innovation: Creators go back to the future, spending almost as much time retrieving once-discarded inventions as they do creating new ones.

For the full story, see:

G. PASCAL ZACHARY. “Ping; Starting to Think Outside the Jar.” The New York Times, SundayBusiness Section (Sun., June 15, 2008): 4.

(Note: ellipses added.)