Shenzhen, China. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Shenzhen, China. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Are starving citizens, or a growing midddle class, more likely to stand up for their rights? In the ongoing debate, here is a bit of evidence in favor of the middle class.

(In economics, a "normal good" is one where, ceteris paribus, more is consumed, when income increases. So in the language of economics, the following article supports the view that political freedom is a normal good.)

(p. A1) When residents here in southern China’s richest city learned of plans to build an expressway that would cut through the heart of their congested, middle-class neighborhood, they immediately organized a campaign to fight City Hall.

Over the next two years they managed to halt work on the most destructive segment of the highway and forced design changes to reduce pollution from the roadway. It became a landmark in citizen efforts to win concessions from a government that by tradition brooked no opposition.

And it was no accident that the battle was waged in Shenzhen, a 26-year-old boomtown that was the first city to enjoy the effects of China’s breakneck economic expansion and that has served as a model for cities throughout the country.

. . .

. . . Possibly the greatest force taking shape here is the quiet expansion of the middle class, thicker on the ground here than perhaps anywhere else in China. This middle class is beginning to chafe under authoritarian rule, and over time, the quiet, well-organized challenges of the newly affluent may have the deepest impact on this country’s future.

”Many people laughed at me, because they don’t have confidence in the government,” said Qian Shengzeng, a 62-year-old former rocket scientist who led the movement against the expressway. ”They think the government is hopelessly rotten. However, our view is that maybe there is a remaining sliver of hope, and the government needs to be pushed.”

In newly rich Shenzhen, as in much of China, social change is being driven by economic transformation and, more than anything else, property ownership.

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

Map showing Shenzhen’s proximity to Hong Kong. Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Map showing Shenzhen’s proximity to Hong Kong. Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

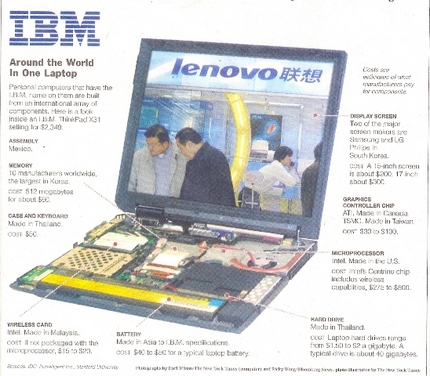

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Close, and distant, maps of the areas effected. Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Close, and distant, maps of the areas effected. Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above. Source of graphic: online version of WSJ article cited below.

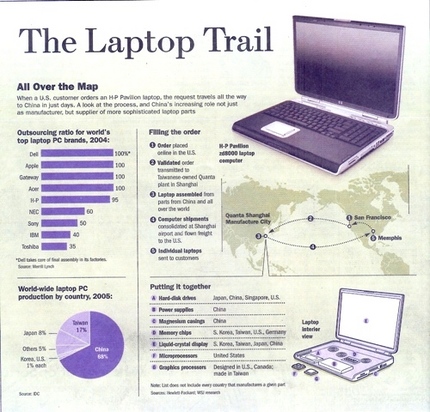

Source of graphic: online version of WSJ article cited below. Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.