Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. A1) WASHINGTON — Is a family with a car in the driveway, a flat-screen television and a computer with an Internet connection poor?

Americans — even many of the poorest — enjoy a level of material abundance unthinkable just a generation or two ago.

. . .

(p. B2) Two broad trends account for much of the change in poor families’ consumption over the past generation: federal programs and falling prices.

Since the 1960s, both Republican and Democratic administrations have expanded programs like food stamps and the earned-income tax credit. In 1967, government programs reduced one major poverty rate by about 1 percentage point. In 2012, they reduced the rate by nearly 13 percentage points.

As a result, the differences in what poor and middle-class families consume on a day-to-day basis are much smaller than the differences in what they earn.

“There’s just a whole lot more assistance per low-income person than there ever has been,” said Robert Rector, a senior research fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation. “That is propping up the living standards to a considerable degree,” he said, citing a number of statistics on housing, nutrition and other categories.

. . .

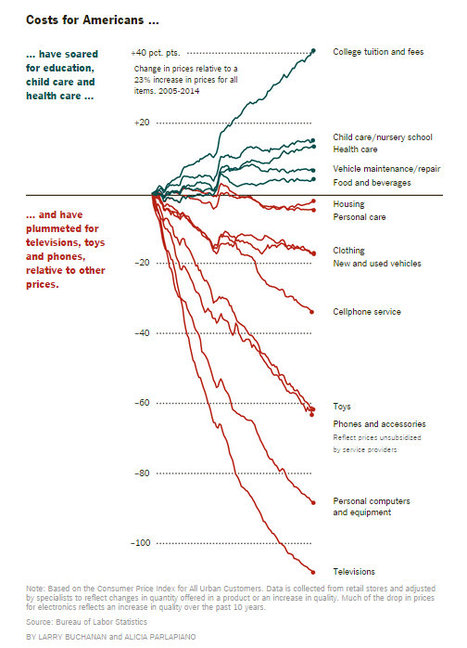

. . . another form of progress has led to what some economists call the “Walmart effect”: falling prices for a huge array of manufactured goods.

Since the 1980s, for instance, the real price of a midrange color television has plummeted about tenfold, and televisions today are crisper, bigger, lighter and often Internet-connected. Similarly, the effective price of clothing, bicycles, small appliances, processed foods — virtually anything produced in a factory — has followed a downward trajectory. The result is that Americans can buy much more stuff at bargain prices.

For the full story, see:

ANNIE LOWREY. “Changed Life of the Poor: Better Off, but Far Behind.” The New York Times (Mon., May 1, 2014): A1 & B2 (sic).

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date APRIL 30, 2014, and has the title “Changed Life of the Poor: Better Off, but Far Behind.”)