Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. C7) . . . , Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers argue that money indeed tends to bring happiness, even if it doesn’t guarantee it. They point out that in the 34 years since Mr. Easterlin published his paper, an explosion of public opinion surveys has allowed for a better look at the question. “The central message,” Ms. Stevenson said, “is that income does matter.”

To see what they mean, take a look at the map that accompanies this column. It’s based on Gallup polls done around the world, and it clearly shows that life satisfaction is highest in the richest countries. The residents of these countries seem to understand that they have it pretty good, whether or not they own an iPod Touch.

If anything, Ms. Stevenson and Mr. Wolfers say, absolute income seems to matter more than relative income. In the United States, about 90 percent of people in households making at least $250,000 a year called themselves “very happy” in a recent Gallup Poll. In households with income below $30,000, only 42 percent of people gave that answer. But the international polling data suggests that the under-$30,000 crowd might not be happier if they lived in a poorer country.

. . .

Economic growth, by itself, certainly isn’t enough to guarantee people’s well-being — which is Mr. Easterlin’s great contribution to economics. In this country, for instance, some big health care problems, like poor basic treatment of heart disease, don’t stem from a lack of sufficient resources. Recent research has also found that some of the things that make people happiest — short commutes, time spent with friends — have little to do with higher incomes.

But it would be a mistake to take this argument too far. The fact remains that economic growth doesn’t just make countries richer in superficially materialistic ways.

Economic growth can also pay for investments in scientific research that lead to longer, healthier lives. It can allow trips to see relatives not seen in years or places never visited. When you’re richer, you can decide to work less — and spend more time with your friends.

Affluence is a pretty good deal. Judging from that map, the people of the world seem to agree. At a time when the American economy seems to have fallen into recession and most families’ incomes have been stagnant for almost a decade, it’s good to be reminded of why we should care.

For the full commentary, see:

DAVID LEONHARDT. “Economic Scene; Money Doesn’t Buy Happiness. Well, on Second Thought . . . .” The New York Times (Weds., April 16, 2008): C1 & C7.

(Note: ellipses in text added; ellipsis in title in original; the title in the online version was “Economic Scene; Maybe Money Does Buy Happiness After All.” )

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

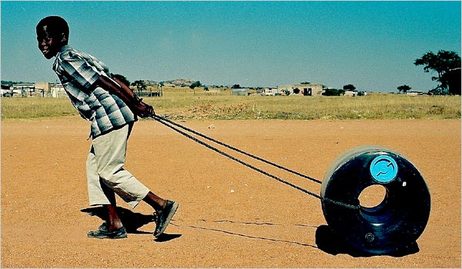

The photo on the left shows a woman safely drinking bacteria-laden water through a filter. The photo on the right shows a "pot-in-pot cooler" that evaporates water from wet sand between the pots, in order to cool what is in the inner pot. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

The photo on the left shows a woman safely drinking bacteria-laden water through a filter. The photo on the right shows a "pot-in-pot cooler" that evaporates water from wet sand between the pots, in order to cool what is in the inner pot. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.