Entrepreneur Kyle Kimmerle at one of his 600 uranium claims. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Entrepreneur Kyle Kimmerle at one of his 600 uranium claims. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Kyle Kimmerle is an entrepreneur, risking his own money. If he guesses right, he will make himself rich, by helping provide the fuel needed for generating electricity for us.

(p. C1) . . . Prices for processed uranium ore, also called U308, or yellowcake, are rising rapidly. Yellowcake is trading at $90 a pound, nearing the record high, adjusted for inflation, of about $120 in the mid-1970s. The price (p. C4) has more than doubled in the last six months alone. As recently as late 2002, it was below $10.

A string of natural disasters, notably flooding of large mines in Canada and Australia, has set off the most recent spike. Hedge funds and other institutional investors, who began buying up uranium in late 2004 to exploit the volatility in this relatively small market, have accelerated the price rally.

But the more fundamental causes of the uninterrupted ascendance of prices since 2003 can be traced to inventory constraints among power companies and a drying up of the excess supply of uranium from old Soviet-era nuclear weapons that was converted to use in power plants. Add in to those factors the expected surge in demand from China, India, Russia and a few other countries for new nuclear power plants to fuel their growing economies.

“I’d call it lucky timing,” said David Miller, a Wyoming legislator and president of the Strathmore Mineral Corporation, a uranium development firm. “Three relatively independent factors — dwindling supplies of inventory, low overall production from the handful of uranium miners that survived the 25-year drought and rising concerns about global warming — all have coincided to drive the current uranium price higher by more than 1,000 percent since 2001.”

. . .

. . . “We won’t build a new plant knowing there’s nowhere to put the used fuel,” Mr. Malone of Exelon said. “We won’t build one without community support, and we won’t build until market conditions are in place where it makes sense.”

But that is not holding back Kyle Kimmerle, owner of the Kimmerle Funeral Home in Moab. Mr. Kimmerle, 30, spent summers during his childhood camping and working at several of his father’s mines in the area. In his spare time he has amassed more than 600 uranium claims throughout the once-productive Colorado Plateau.

“My guess is that next year my name won’t be on the sign of this funeral home anymore and I’ll be out at the mines,” he said.

He recently struck a deal with a company to lease 111 of his claims for development. The company, new to uranium mining, has pledged $500,000 a year for five years to improve the properties. Mr. Kimmerle will receive annual payments plus royalties for any uranium mined from the area.

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

Yellowcake, which is processed uranium, is in the third jar from the left of the top photo. The photo below it is of old equipment at a dormant uranium mine. Source of the photos and the graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Yellowcake, which is processed uranium, is in the third jar from the left of the top photo. The photo below it is of old equipment at a dormant uranium mine. Source of the photos and the graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

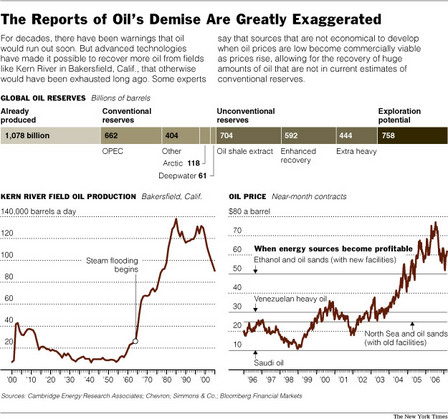

Kern River pipelines in front, and pump in back. Source of graphic and photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Kern River pipelines in front, and pump in back. Source of graphic and photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Work and non-work at Google’s Manhattan offices. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Work and non-work at Google’s Manhattan offices. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Photo on left is a Borders store; image on right is of Borders CEO George Jones. Source of photo and image: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Photo on left is a Borders store; image on right is of Borders CEO George Jones. Source of photo and image: online version of the WSJ article cited above. Randall Moorehead’s Phillips Electronics wants the government to force us to switch from the incandescent bulb on the left, to bulbs like the Phillips bulb on the right. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Randall Moorehead’s Phillips Electronics wants the government to force us to switch from the incandescent bulb on the left, to bulbs like the Phillips bulb on the right. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.